Joe Pokay hasn’t found a “one-size-fits-all” plan for regenerative grazing. He’s discovered the opposite. The seven Noble Ranches he oversees — nearly 14,000 acres in all — are anything but uniform in terrain, grass species, soils or infrastructure. Each needs a grazing management plan tailored to the territory.

Noble’s largest property, the Oswalt Ranch, is near Marietta, Oklahoma. It’s almost all native range with warm- and cool-season prairie grasses; rough, rocky topography with creeks and gulleys; with 50% of the total acres grazeable for the cow-calf and stocker operations. It’s now also home to Spanish goats that help with brush encroachment.

Then there’s the Red River Ranch. Bordered by the Red River on the south, it’s mostly level, sandy terrain — vulnerable to both flooding and wind erosion — with a lot of introduced grasses, mainly bermudagrass. The majority is grazeable, including the 450-acre pecan orchard, one of the oldest improved orchards in the state. Noble runs a cow-calf operation at Red River, adding stockers seasonally, and has introduced sheep as an enterprise this year.

The big thing is just being out there. it’s really important to spend some time with your livestock, because their behavior will tell you more than anything.”

Joe Pokay

“They’re completely different ranches,” Pokay says. “The goals are the same — we want to improve soil health and make sure our animals are performing at the level we want. We adhere to the same principles, but we go about them in completely different ways.”

By principles, he’s referring to the six soil health principles: know your context; cover the soil; minimize soil disturbance; increase diversity; maintain continuous living plants/roots; integrate livestock.

“The beautiful thing about the principles is it (the terrain) doesn’t really matter,” Pokay says. “They’ve worked in just about any environment you can imagine, from the Chihuahuan Desert to Alberta. The principles are few, and that makes them easy to adhere to.” Just be sure to follow the principles, he says, and good things should follow.

That being said, following the principles on each of the seven ranches with a 15-person ranch team takes planning and coordination. That’s where the grazing management plans come in, and the art of matching plan to property.

The Grazing Management Plan

“The overall goal for the grazing plan simply is to manage our grazing to allow for adequate recovery of plants,” Pokay says. “So, we want to eliminate overgrazing, and overgrazing is a function of time, not necessarily stocking rate or stock density.

“Our whole goal is to be able to have our animals perform and, through our management of grazing, to improve the land and improve the soil,” he says. “Done successfully, this in turn improves grazeable acres, improves the quality of forage and improves animal health, as well.”

Another way of looking at the grazing plan’s purpose is to have it “mimic the herds of bison that used to roam the prairie,” Pokay says. They grazed an area and moved on, letting the native prairie grasses recover for long periods before they were grazed again.

7 Things to Include in a Grazing Plan

- Goals

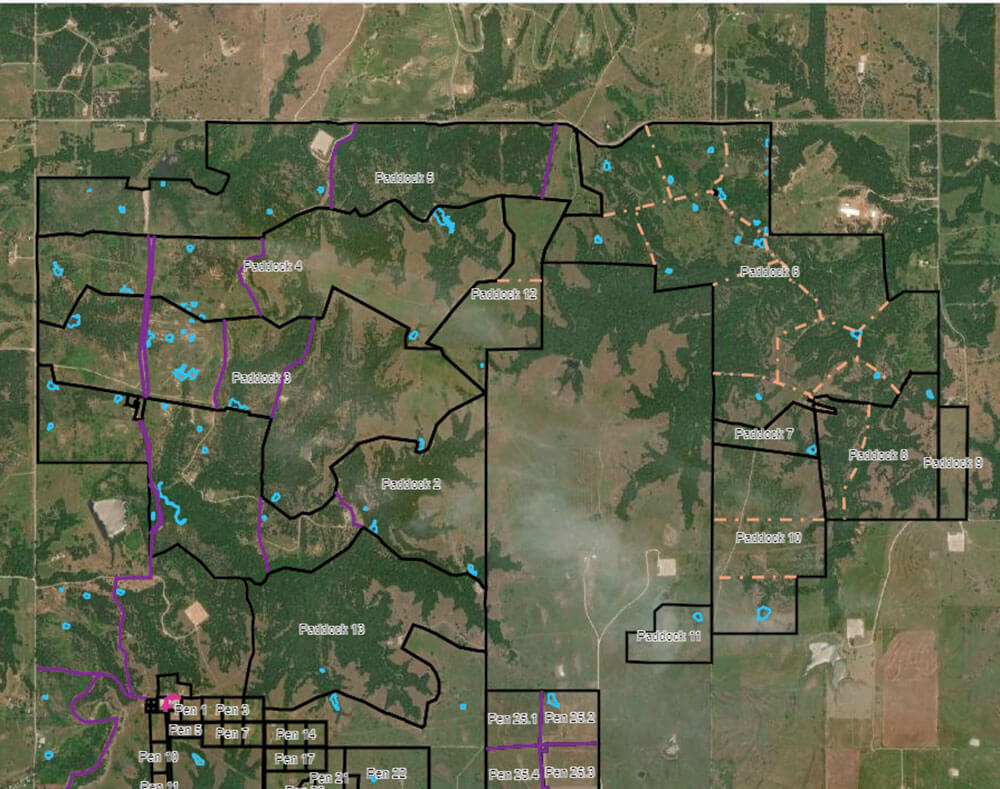

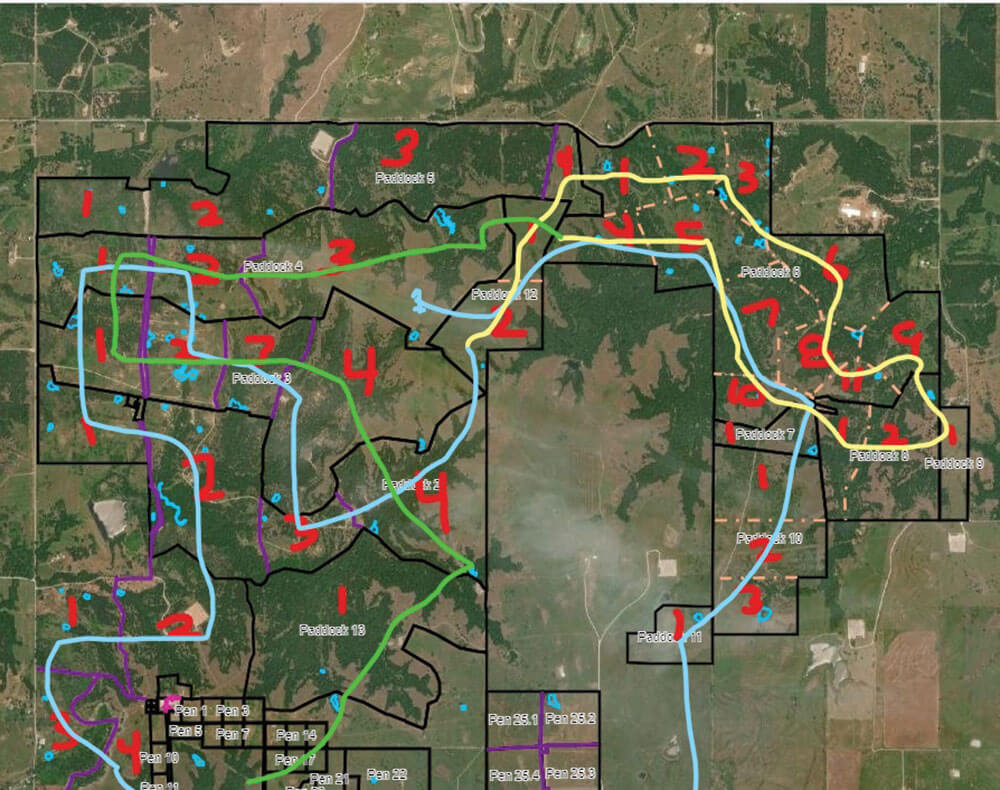

- Maps

- Existing infrastructure

- Existing forage types and production

- Grazeable acres

- Potential stocking rates

- Any additional equipment or infrastructure needs

On today’s ranches, it takes careful planning to emulate what the bison did naturally. “Our main goal is not to come back to an area before the plants are recovered from the previous grazing event,” he says. “When the grass is growing quickly, we don’t need as much rest. And when it’s growing slowly, we need longer rest. If the grazing event is in August, the plants might not be fully recovered until June the next year.”

By recovery, Pokay means watching for the plants to begin their reproductive stage, which is a good sign that the roots have recovered and built up reserves. They keep records of the grazing and recovery periods for each pasture to help predict how long they can graze the next year, if conditions are similar.

Recovery periods vary seasonally, as well as by location, as the forages grow at different speeds. “There are some places, like at the river, where the introduced grasses recover a lot faster. So (ranch manager) Kevin Pierce’s recovery period at Red River is usually a lot shorter than our recovery period on the native range at Oswalt.”

Pokay says they plot out grazing for the entire year, planning for recovery periods and areas where they will stockpile forage for the dormant season.

“We also want to plan to not graze the same areas at the same time of year all the time.” While each ranch’s grazing plan covers a year at a time, “we also iterate it a lot, depending on how things are growing and if we’re sticking to our plan, or if we’re moving faster or slower than the plan called for.”

There are other practical aspects to the plan, based on the layout of the ranch, he says.

“We really try to focus on having our grazing plan match up to when we’re going to be near a set of pens. So, if we need to wean or ship or pregnancy check or something, we filter our plan through those needs.” Pokay also says they are using more portable tanks with quick-connect couplers along the water pipelines so they can adapt to multiple grazing locations rather than work around permanent water sites.

“The problem with permanent anything is when cattle use an area all the time, they hurt the ground and kind of wallow everything out,” he says. However, there are times they may want the herd effect of hooves to break up capping on bare soil and jumpstart its recovery, or to stamp down brushy areas to add both ground cover and organic matter to the soil.

Working the Plan

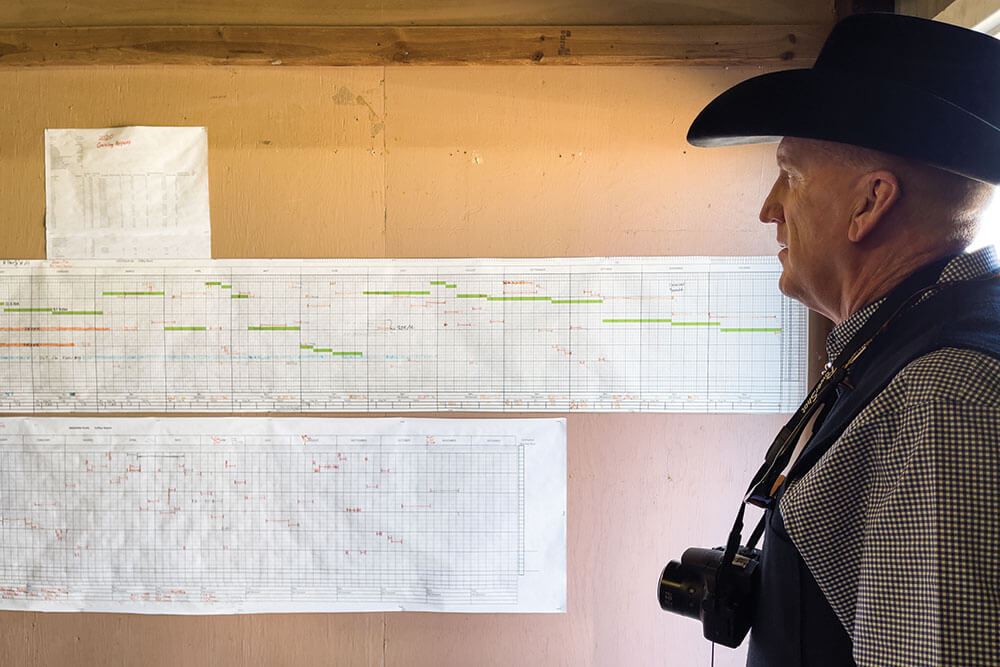

Once the grazing plans are set, the managers use the grazing charts to guide the graze timing and pasture moves.

“It’s understood that if we have a big pasture and the grazing plan says we’re going to stay in there for five days, that means we’re going to move ‘em five times. That’s just inherent in our grazing management, as we try to move animals at least once a day,” Pokay says. And yet, it’s not as simple as that. For example, deciding on the size of a paddock for a particular day.

“It really depends on what our goal is for that graze, and if we’re trying to have high animal impact or if we’re trying to add more performance,” he says. “The size of our grazing is more dependent on what the animal needs, so we’ll go out and figure out how much grass there is in that paddock, and then we figure out how much the animal needs for that day.

“We always plan to leave some residual behind and keep the soil covered, so we don’t want to take every possible thing out of it. Yet we want to give ‘em as much as they need every day. Sometimes it’s two or three days between moves, and sometimes we move them more than once a day.”

The Art of Grazing

Pokay likes to call what they do the art of grazing because you have to take in and consider everything. It doesn’t work to just say “this is how you do it” and blindly follow a strict plan. There’s no “one thing” to watch and then do “X.” It matters if it’s intensely hot or windy or humid. And it matters what the animals are telling you.

Noble ranch team members check their animals every day, making sure they have two or three days’ worth of grass on weekends. They also make it a point to visit each other’s ranches, observing and talking through approaches as they hone their eyes and their art.

“The big thing is just being out there,” Pokay says. “You can’t just drive by and look at the grass and leave. It’s really important to spend some time with your livestock, because their behavior will tell you more than anything. If you go out there in the afternoon and they’re milling around, and they don’t have a very full gut and they’re just kind of antsy, that’s probably a cue that you need to move them regardless of whether you think there’s enough grass or not.”

As the cattle have adapted to regenerative grazing, their tastes have evolved. “Cows only work as hard as you ask them to. If they have 5,000 acres to graze around, they’re only gonna eat ice cream the whole time.” So, by limiting the area, it pushes cattle to seek out and eat more forbs with medicinal and anti-parasitic properties and helps them regain a more natural instinct of what to eat.

Adapting to Differences

As mentioned earlier, the physical differences between the Oswalt and Red River ranches call for different grazing plans and tactics.

Because it’s easier to see and to get around with no hills and few trees or brush in the way at Red River, “we can really hone in on how much we want the cattle to have for a certain number of hours and really control the time of day we move them,” Pokay says. “It’s easier to get around and move the cows there than it is at Oswalt.” On the hillier ranch, the terrain makes it harder to move cattle multiple times a day or even daily.

As long as we can keep the soil from going bare, we can give it enough rest to keep something growing. that’s a challenge specifically for the river ranch.”

Joe Pokay

Not that grazing at the river is easy. “We have to plan for shade in the summer, so we’ll graze in the pecan orchards.” This “silvopasture” approach has the added benefit of providing natural fertilizer for the pecan trees, which tend to be a high-input crop.

Red River Ranch has suffered areas of large wind erosion at times, but using cover crops to keep living roots in the ground helps. “As long as we can keep the soil from going bare, we can give it enough rest to keep something growing. That’s a challenge specifically for the river ranch.”

Planting season-specific crops helps maintain a living root and keeps the soil microbiology thriving. In addition, some of these cover crops can get big, he says. That not only helps feed the cows, “but also gives us something to knock down and put on top of the soil to keep it covered. Bare soil is the enemy.” And the multi-species, diverse mix of cover crops, “also increases our plant diversity, which is good for the soil life.”

This year’s grazing plan for Red River included a new species — sheep. “Sheep graze differently than cows, so sheep will help with the forbs and all those kind of things that come up,” Pokay says. “Plus, it gives us another enterprise to stack on the same acres to help with the profitability.”

Keeping Track

To help track profitability and other metrics, Noble uses a cloud-based livestock farm management software system called AgriWebb. It manages data for animal production, pasture movements, health records and feeding records on an individual-animal basis.

“Whenever we move them, we track what our stock density was and animal units per day per acre (total animal units times the number of days grazing divided by the acres), because that will tell us our consumption.” Knowing the consumption for each graze lets him compute forage production and recovery time, which informs future grazing planning.

For Noble, knowing performance and cost per animal allows the managers to match animal performance to specific management styles and conditions on the ranches. With that information and ecological site monitoring, Pokay says, “we’ll be able to put numbers to regenerative ways to ranch profitably while improving soil health.”

Comments