Over the years I have seen many grazing operations in many parts of the country. I have seen places that never seem to grow as much grass as they should, and I have seen places that always seem to have lots of grass. Likewise, I have seen places that have been hurt by the extreme weather of the past several years, and I have seen places that have tolerated the extreme weather quite well. The places that have lots of grass and are doing well don’t necessarily have better soil or get more precipitation, and they may not be stocked lighter or rested more days per year. So what is the difference? Roots and the effects that management has on the roots.

I’ve always kind of known that grazing management affects roots, but it was made crystal clear to me this past summer when I was introduced to some work published by F.J. Crider in 1955. Through several experiments using various perennial grasses, he showed the effects that forage removal has on root growth.

In one experiment, Crider showed that when more than half of the forage is removed from a plant, root growth stops within the first day or two afterward and stays stopped from six to 18 days, with an average of 11 days. In the real world, this means if cattle have the opportunity to graze more than half of the top growth of a grass, at an interval less than 11 days, the roots never get to recover. If the roots don’t recover, then eventually neither will the top.

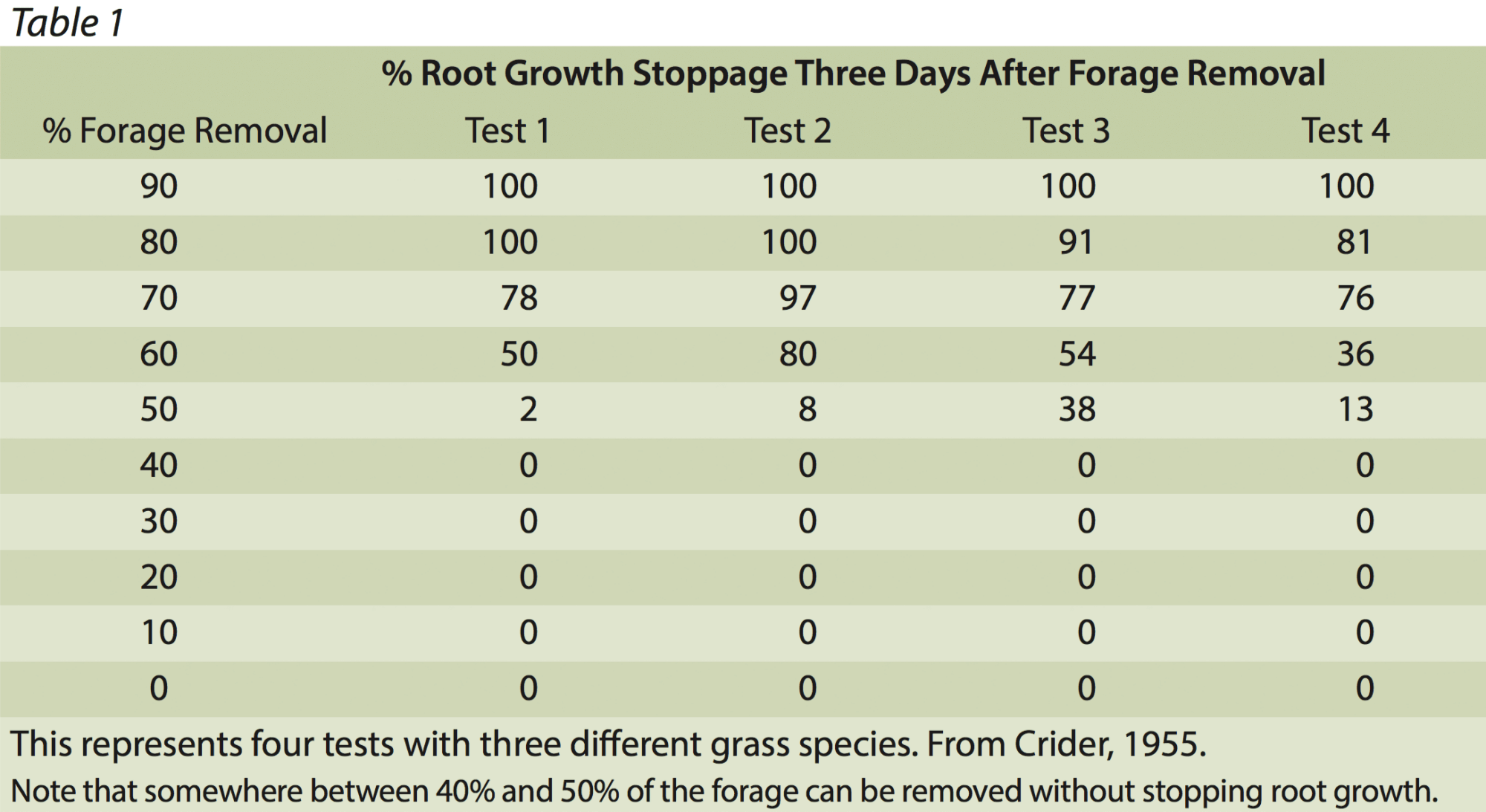

In another experiment, Crider showed the effect that a single removal of top growth, in 10 percent increments, has on root growth. When 40 percent or less of the forage is removed, 0 percent of the roots stop growing. When 50 percent or more of the forage is removed, an increasing percentage of the roots stop growing. When 90 percent of the forage is removed, 100 percent of the roots stop growing (Table 1). In other words, leaving more than half of the forage any time a plant is grazed during the growing season allows the roots to continue to grow. If the roots keep growing, so should the forage.

Not only did higher percentages of forage removed result in greater percentages of roots that stopped growing, the higher percentages of forage removed also resulted in greater lengths of time before the roots resumed growth. Thirty-three days after top growth removal, plants with 80 and 90 percent of their forage removed still had a portion of their roots that had not resumed growth.

In a companion experiment, Crider showed how repeated removal of forage affects root growth. Like the previous experiment, removal of a percentage of top growth, in 10 percent increments, was done. However, in this experiment, forage was repeatedly removed to the height of the initial removal three times per week for five weeks. This time, 33 days after initial top growth removal, plants where 50 percent or more of their forage was removed still had a portion of their roots that had not resumed growth, and none of the roots had resumed growth on the plants with 70 percent or more of their forage removed.

So removing half or more of the forage at a time stops root growth whether cattle graze rotationally or continuously. However, leaving half or more of the forage allows root growth to continue uninterrupted. If the roots grow more, the forage grows more; in the long run, more forage will come from the half that is grazed.

The entire article by Crider can be found by looking up Root-Growth Stoppage Resulting From Defoliation of Grass by Franklin J. Crider, Technical Bulletin No. 1102, United States Department of Agriculture, February 1955.

Comments