There are moments of pure bliss out on the open prairie.

A feeling of freedom, where peace arises from watching the cattle graze on gently rolling hills. There is satisfaction in making an unproductive piece of land spring to life again and in guiding an animal to meet its potential, knowing the act of working with nature is the basis for nourishing nations.

But there are also nights when temperatures drop and calves come anyway. Days when the drizzling rain makes tagging those new babies miserable. Fences break at the weight of an ornery steer, and drought dries up his food. Then the rains come but the rivers rise. The harvest spoils, and the bank note comes due.

“What next?”

“How am I going to get through?”

These are the questions for which the Noble Research Institute seeks answers. For the moment of frustration but, more important, to help prevent the crisis. Weather and markets can’t be controlled, but risks can be managed and tools developed so that farmers and ranchers can make intentional decisions for their land and operations.

It takes a team of people from across the planet to dig up knowledge and turn it into resources for producers. This quest is just as much personal as it is professional for many at the Noble Research Institute. Sometimes they, too, are the producers striving to improve their operations.

They may have grown up on farms or ranches just down the road or on another continent. They may unravel mystery behind the microscope or out in the fields. Either way, they share a deep-rooted desire to serve producers. Agriculture is not just a job for them. It’s in their veins.

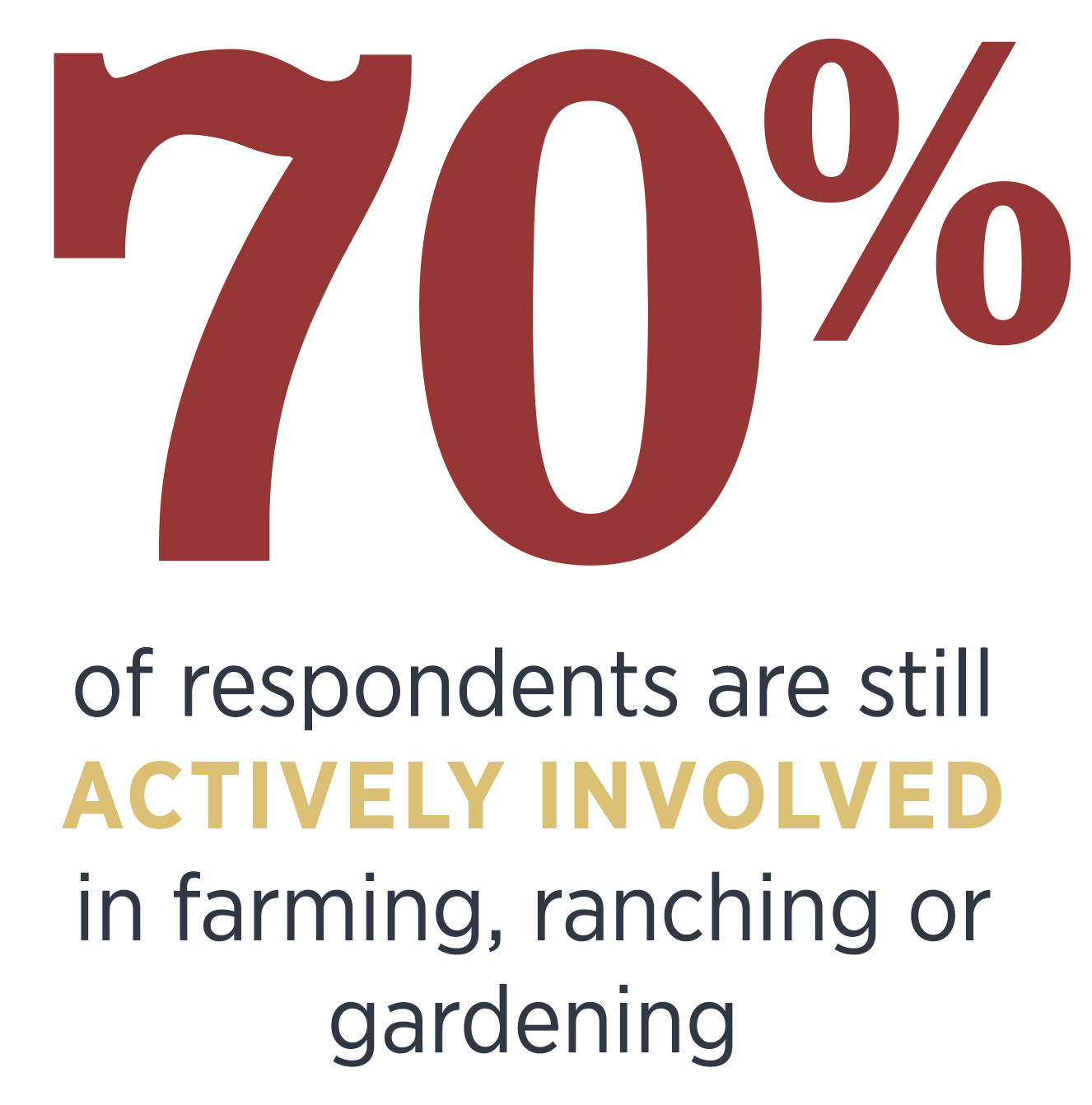

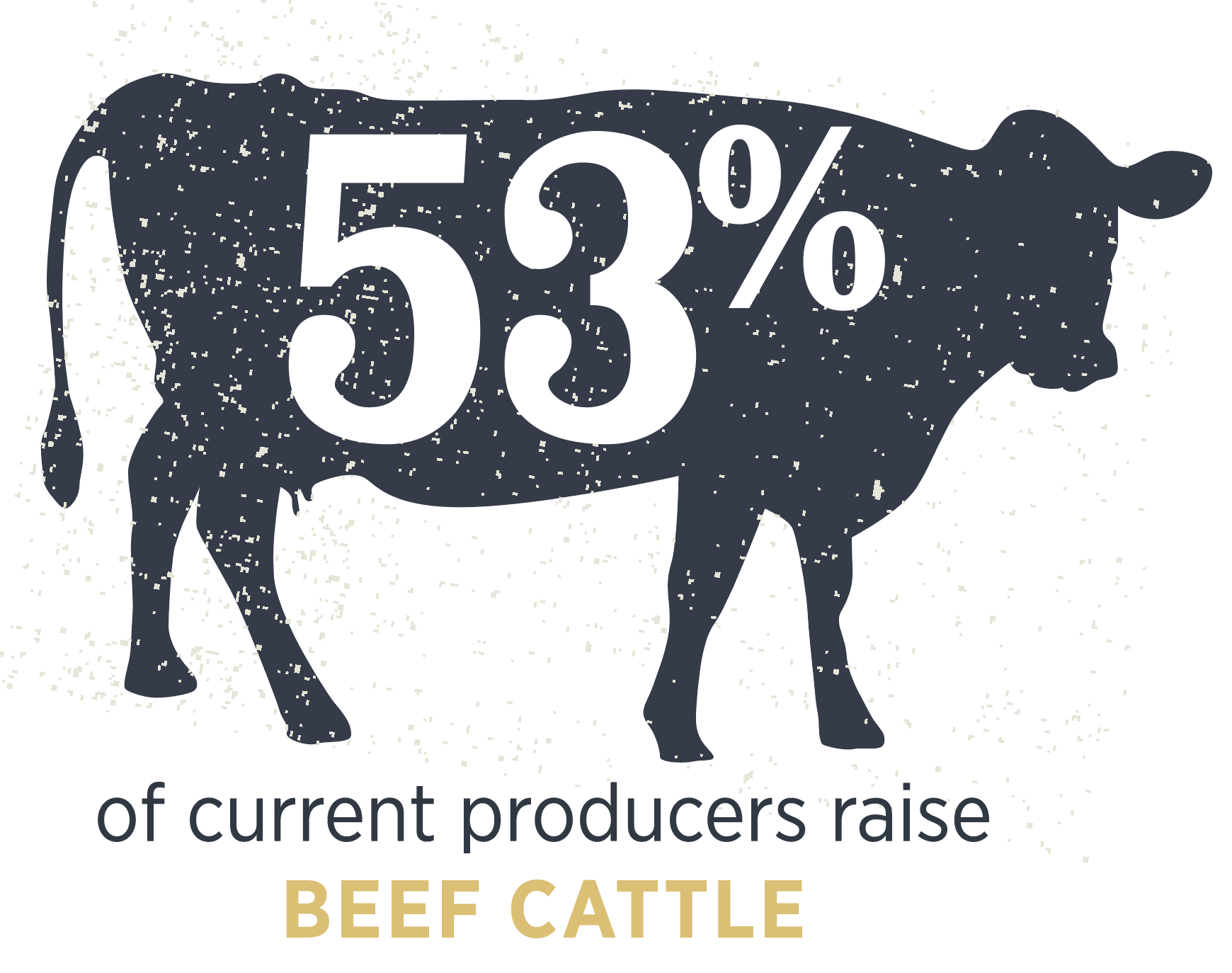

By the Numbers

A total of 57 employees shared their personal stories of growing up on farms and of their current involvement in production agriculture.

A Noble Cause

Delivering solutions to great agricultural challenges is a personal mission for many at Noble.

Tim Boatright grew up on a beef cattle, corn and cotton farm in Littlefield, Texas, and now maintains and repairs tractors and other equipment at Noble.

“I became a John Deere technician because I saw how important the support of farming was — and is — to production agriculture.”

Gayle Donica, human resources manager, grew up on a ranch in southeastern Oklahoma and now manages stocker cattle with her husband, Kent.

“Knowing the risk, struggles and challenges in the ranching industry, and having a personal stake in producing beef, gives me great appreciation for what the Noble Research Institute does. It helps me not only understand what we as an organization are trying to accomplish, but also what other farmers and ranchers are up against.”

Robert Williams, safety and risk manager, grew up on a small beef cattle operation on the 120-acre farm that his grandfather started in Overbook, Oklahoma.

“Being part of an organization that supports the family farm is very important to me.”

Larry York, Ph.D., grew up tending horses in London, Kentucky, and now gardens with his wife, Xinji, and their 4-year-old daughter, Wanda.

“While I didn’t grow up in production agriculture, I appreciate the hard work involved from years of breaking ice in the horse trough, throwing bales into the loft and feeding no matter the weather. Growing up in the country around ‘real’ farmers gave me an appreciation for their labor as well as for nature.”

Ranch to Noble Ranch

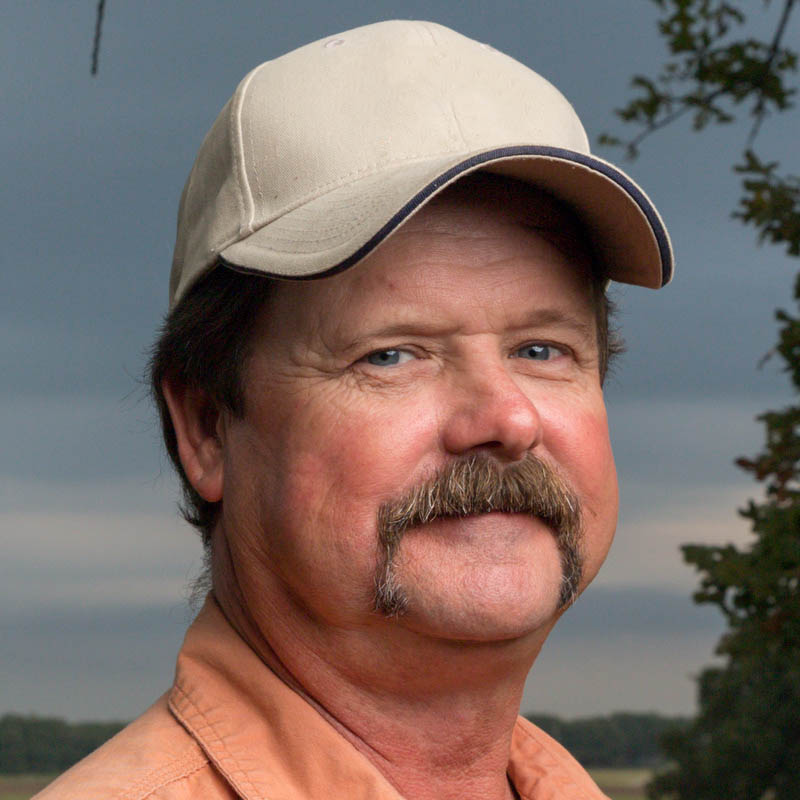

Mid-February rains have given way to a day of sunshine, and Devlon Ford isn’t wasting it.

Ford sets his laptop on a work-worn metal table next to the cattle chute at Noble’s Oswalt Ranch while other cowboys ready a group of heifers that had come in from Valentine, Nebraska, four days before. They had been waiting for better weather to work with the young females.

“They came off the truck looking pretty good,” Ford had said earlier of the cattle that will soon graze different forages as part of a project led by Twain Butler, Ph.D. They may also become part of studies that look at how to develop heifers into cows that stay in the herd longer.

Ford wears a pair of black gloves with “Oklahoma Beef Quality Assurance” written across them and the tip cut out of the right pointer finger. He laughs, calling them his “specially modified gloves.” They make it easier to poke numbers — data points, like weights — into the computer.

Ford grew up just 30 miles away, in Lone Grove, Oklahoma, and spent much of his younger years on his grandparents’ land outside of nearby Springer. His mother’s family raised horses and rodeoed, while his father’s family raised cattle and farmed.

“As I grew older, I became more interested in the cattle side of livestock,” Ford says, “and, although I seldom have the opportunity, I still enjoy being mounted on a good horse to work cattle.”

Ford was only 24 years old when he started working on Noble’s Pasture Demonstration Farm, just north of where he grew up. However, he had already spent nearly a decade working on different operations with cattle, from Longhorn to Simbrah, beyond his family’s ranch.

The best part of what we do is helping producers. I’m in the background; the consultants and researchers design the projects, and we do the work on the ranches. But eventually what we learn out here can be taken to the producer.”

Devlon Ford

In those first few years at Noble, Ford stayed many late nights in the tractor planting wheat and rye for stockers. Often, he wouldn’t go home until 8 or 9.

Gradually, he became more involved with keeping the cattle records. Today, he is a go-to person for those wanting to know how many cattle are on Noble’s 14,000 acres of research and demonstration land (1,601) or how many calves have been born (159 from Jan. 9 to Feb. 22). He can also tell the story of each cow, through numbers and personal experience, and how she contributes to research just by doing her thing — eating and raising calves.

“The best part of what we do is helping producers,” Ford says. “I’m in the background; the consultants and researchers design the projects, and we do the work on the ranches. But eventually what we learn out here can be taken to the producer.”

Ford’s home base is Coffey Ranch, one of seven Noble properties, where he can watch some of the herd from his front porch. The ranch is where he and his wife, Tina, raised their two sons. But 45 minutes away, Ford also runs his own cattle on his father’s portion of the family land. The small herd is largely built from heifers his kids showed in their 4-H and FFA days, though this fall he plans to sell the cows and start fresh.

“Right now, it’s not an economically sustainable operation,” Ford says. “I want to get in and do some of the things we talk about here at Noble.”

That starts with the soil, he says. He’ll clean up the property and reorganize fences so that he can better manage rotational grazing when he puts cattle back on the land. He plans to work with soils and crops consultants to start rebuilding organic matter. And, before bringing cattle back, he wants to run different marketing scenarios with the economics consultants to see what would work best for his management style and time limitations.

“I like working with the cattle, and I like working with people who like working with the cattle,” Ford says. “But I also want to improve the quality of land that my grandfather worked so hard to buy and make a living off of.”

Cattle Calculations

Numbers come naturally to Myriah Johnson, Ph.D. After all, she’s been counting cows since she was 2 years old.

Johnson grew up on a 2,000-acre wheat, cow-calf and stocker operation in north-central Oklahoma, where her father and brother continue to farm and ranch. She smiles, remembering her early years of tending bottle calves and following her dad out to the pasture to feed cattle.

In high school, the farm girl excelled in math. Calculus. Statistics. All of it. But she knew she wanted to remain involved in agriculture. During her search for a college major, agricultural economics seemed like the obvious choice.

“I thought, ‘This is the ag field that does math, so that’s what I’m going to do,’” she says.

Johnson went to Oklahoma State University, just 30 minutes from home. During her first semester, she took an ag econ class with Derrell Peel, Ph.D., who uses his livestock marketing and risk management insights to serve Oklahoma producers. From that first day, she thought: “Yep. This is where I’m supposed to be.”

Life Lessons

Some of the greatest products that come off the farm or ranch are character qualities and skilled people.

Becca McMillan, senior administrative assistant, grew up around horses and goats and her husband, Zeno, grew up around cattle, chickens and goats in Mason, Texas, where his family also produced wheat and peanuts. They now raise cattle and goats with their 9-year-old daughter, Rory, on their ranch near Mannsville, Oklahoma.

“I believe growing up on a ranch teaches kids to be more responsible at an early age. Having animals depend on you invariably builds character, morals and values.”

Ronald Trett grew up on a family dairy in rural south-central Oklahoma, and he has also managed a commercial cow herd of his own and haying operations of around 1,200 acres. He currently manages cattle and forages on Noble’s Ardmore-area farms.

“Coming from a farming and ranching background gives you a different outlook on life. It has taught me perserverance over the years.”

Hugh Aljoe, director of producer relations, grew up on the family farm in Roscoe, Texas, and worked on several other farms and ranches as well as at cattle auctions before becoming a ranch manager at Marquez, Texas, after college.

“Raising a garden and constantly working with livestock throughout my youth taught me much about work ethic, animal husbandry and agriculture in general.”

Chloe Jones, social media coordinator, grew up raising cattle in Rising Star, Texas, where her family also grows corn, peanuts, cotton and milo. She and her husband are developing their own herd outside of Ardmore, Oklahoma.

“Growing up on a ranch taught me the value of hard work and to love and take care of the land and its animals.”

“Farmers and ranchers have so many things they have to be … I feel like that’s where I can be useful: I can do the deep dive and provide that information they need to make decisions.”

Myriah Johnson

After earning her master’s in ag economics and doctorate in animal science at Texas A&M, Johnson joined the Noble Research Institute as an agricultural economics consultant in 2016.

One of her responsibilities is to analyze information collected as part of a national beef sustainability pilot project, which follows calves all the way through the beef value chain, from the ranch to the feedlot to the packer, processor and ultimately McDonald’s. She studies the data, looking for clues that help her build recommendations on how producers can be more efficient on their operations.

“Farmers and ranchers have so many things they have to be: animal nutritionists, agronomists, mechanics, marketers,” Johnson says. “They don’t have time to be a mile deep in all those things. I feel like that’s where I can be useful: I can do the deep dive and provide that information they need to make decisions.”

While Johnson has been known to spend vacation days on her family’s farm planting wheat and weaning calves, most of her contributions are made at the computer 150 miles south. She runs numbers, helping her father and brother decide on insurance programs and marketing strategies. In the last two years, they have gone from marketing calves at the sale barn to directly selling to the feedyard, and they continue to look into other options, such as retaining ownership of calves as they gain their final pounds.

Staying in tune with her family’s cattle operation helps her assist not only them but also other producers because the more data she can pore over, the more complete a story she sees.

She knows her family’s herd health protocol is similar to that of many producers who work with Noble. So when she sees some cattle getting sick in the feedyard while others don’t, she is able to look at other factors (like age, weather and genetics) to get a better picture of what might be going on — and what adjustments can be made to keep cattle healthier.

“Our work is tailored to answering important questions that require a lot more time and resources than any one person could give on their own,” Johnson says. “I’ve always had an internal feeling that whatever I do, I want it to apply back to the farm, and I never want to stray from that.”

Lifestyle Yields Tasty Rewards

As a child, Tabby Campbell spent time on her grandfather’s small farm in Enville, Oklahoma. Today, she continues to grow fruits and vegetables in her backyard, and she supervises the Ag Services and Resources Core.

“My grandfather raised chickens for eggs and meat; a cow for milk, butter and cream; hogs for pork; and vegetables to eat as well. He lived a very simple life, and I loved being with him. He raised bees for honey and had a small pond that provided us with an occasional fish dinner. He was a man of God and depended on the land to take care of him and his family. More recently, I’ve done a little research myself. I grew new potatoes in a pile of hay covered with hog wire. Once the potatoes started making large vines, they came up through the hog wire. I was able to lift the wire up like a car hood and pick some potatoes for supper. I find growing my own food very rewarding, and I like to try new things to improve my crops.”

Tim Woodruff’s family gardened and raised a billy goat and 25 egg-laying chickens in the backyard of their home, in an Atlanta suburb. He now serves as a web designer.

“My family’s interest in agriculture was only a hobby, but we enjoyed being able to have eggs and vegetables to supplement our groceries.”

To Solve Hunger

Venkatachalam Lakshmanan, Ph.D., grew up following his grandfather across the red loamy land his family has farmed since 1901.

As a child, he would dart out of school every day to help his “ayya” tend goats or work in the fields of their remote village near Oddanchatram, Tamil Nadu, about 200 miles from the southernmost tip of India. When the elder man hitched up the ox to plow, Lakshmanan would go with him. When it was time to irrigate, the young boy would let his grandfather know when the well water had filled one plot and it was time to move to the next.

“I was involved in all aspects of farming,” says Lakshmanan, whose village is home to about 80 families, all of whom grow food on 2 to 20 acres.

After finishing fifth grade at the local school, Lakshmanan attended high school in town. Every morning, he would ride his bicycle the 2.5 miles to school and return in the evenings. On days when his father sent vegetables — like tomatoes, eggplants, beans, chili peppers and okra — to market, Lakshmanan would stop by to watch them sell and collect the baskets to bring home.

Lakshmanan became the first in his family to go to college, turning down an engineering school in favor of studying agriculture. On his first day of class, he knew he had made the right decision. The teacher walked in and asked, “Why do we need agricultural research?”

“He looked at us and said, ‘Today, 20 million kids in India are going to sleep without food,’” Lakshmanan says. “That’s the moment I knew I wanted to get all of my degrees in agriculture.”

In 2011, he earned his doctorate and went to the University of Delaware to study soil microbes as a postdoctoral fellow. Five years later, he learned of another postdoc position at the Noble Research Institute.

“I knew from my education and working in the fields in India that there was something to soil microbes, something beneficial for plant growth,” Lakshmanan says. “I knew I wanted to do something that would have direct use for farmers, so I thought, ‘OK, I’ll do this.’”

Having the direct contact with farmers is my favorite part of what I do. Helping them is what gives me satisfaction. I am a scientist, but I am a farmer first.”

Venkatachalam Lakshmanan, Ph.D.

He started working with Kelly Craven, Ph.D., who, along with James Rogers, Ph.D., looks at a combination of two agronomic practices, no-till and cover crops, in winter wheat pasture to see how they influence subsequent wheat production, cattle performance and economics. Lakshmanan studies how the practices affect the beneficial microbial communities in the soil. Now in the Functional Genomics Laboratory, led by Michael Udvardi, Ph.D., Lakshmanan is also interested in isolating microbes specific to a particular plant so they could be used to achieve targeted benefits in that crop.

The research has given him opportunities to speak to producers at conferences, like No-Till on the Plains. He shares with them his hope that they will soon be able to test for microbes and know which ones they need to add or reduce based on their soil’s needs.

“Having that direct contact with farmers is my favorite part of what I do,” Lakshmanan says. “Helping them is what gives me satisfaction. I am a scientist, but I am a farmer first.”

On their family land in India, Lakshmanan and his brother continue to manage guava and sapota trees as well as Gloriosa superba, a lily that is highly valued for its medicinal uses. They are also establishing a guava orchard nearby on land they bought three years ago.

Though Lakshmanan is able to visit the farm only once every year or two, he constantly communicates with his brother. He finds his work on microbes too fascinating to give up, but he hopes to someday return to his homeland to continue his research and farming.

For now, he grows traditional Indian vegetables in his Oklahoma garden with the help of his wife, Vidhya Raman, Ph.D., also a postdoctoral fellow at the Noble Research Institute, and their 5-year-old daughter, Aadya Bharathi.

“I started out in agricultural research because I wanted to help with the hunger problem in India,” Lakshmanan says. “Now I also have the opportunity to help farmers and ranchers in the U.S.”

Around the World

Employees come together at the Noble Research Institute from 20-plus countries to carry out the vision of Lloyd Noble.

Yanina Alarcon, grew up following her father, an agronomist, to the field in Argentina. She now studies pecan genetics in hopes of improving disease resistance.

“My father is an agronomist who has a medium-sized company that sells alfalfa, soybean and sunflower seeds as well as agrochemicals. When I was little, he worked as a consultant for a research institute in Argentina. I remember going with him to check on sunflower and soybean field plots or taking soil samples. I was also exposed to people working in the lab, and all that raised questions for me that made me want to get answers through science. I would ask questions like ‘Why do the sunflowers move?’ ‘Why are you taking soil samples?’ and ‘What do you do to the samples?’ It made me a curious person who, at the end, wanted to become a scientist and work on trying to answer some of those questions and, with those answers, help farmers.”

Wangqi Huang, grew up in Poyang, Jiangxi, China, where his family grew rice and raised chickens. He now works in Noble fields as a small grains breeder.

“My experiences taught me how to grow food. My wish is to help farmers improve their income and life quality.”

David McSweeney’s father was a government agriculture adviser in New Zealand who, when he retired, bought a cattle and sheep farm, where the family spent all their spare time. McSweeney manages the acre of grass under glass as biosafety and greenhouse research manager. He also grows herbs in his aerogarden.

“We always had a strong ag background, but our time on the farm really helped me share the passion of those who want to make things happen with the land.”

Yuhong Tang, Ph.D., fondly remembers working alongside her mother in the community field and family vegetable garden during her childhood in Yingjing, Sichuan, China. She now manages the Genomics Core Facility and teaches her children how to grow vegetables in their backyard.

“My childhood helped me develop a love of nature and a compassion for farming and farmers. At the end of the day, we all need to eat. We want to survive and find happiness. We are not so different from each other, and food and agriculture can be a common ground.”

No-Tech, High-Tech

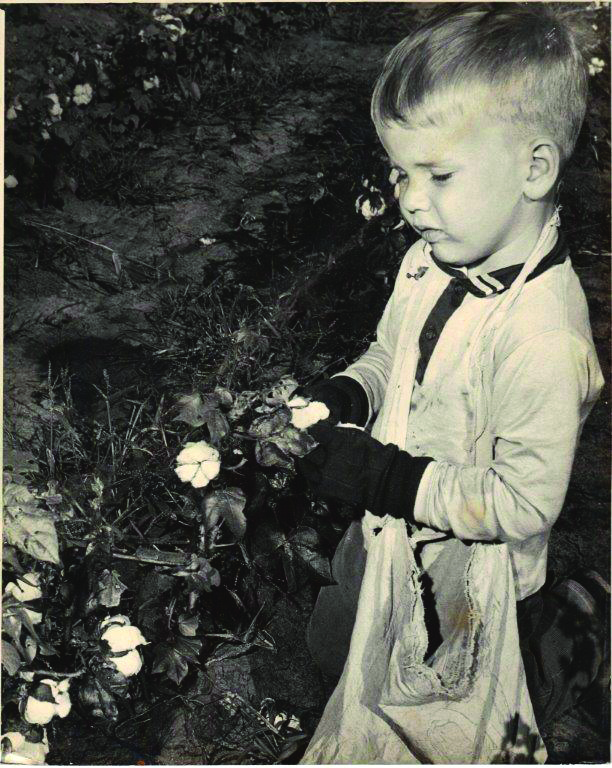

Tresa Trammell was 3 years old when she moved to the C-Bar Ranch in Madill, Oklahoma.

When her father, Alden Combs, a schoolteacher in Carnegie, saw an ad for 1,000 acres, he decided to drive down and see it. Soon after, he took out a loan and moved his wife and three small children into a tiny trailer on the property, 200 miles southwest of the “nice little farmhouse” they had called home.

Combs taught in town and drove a school bus while building up his cow herd and planting pecan trees. The family lived off the land, growing fruits and vegetables to can or freeze. They raised 100 meat chickens every summer and milked their own dairy cow to churn butter.

“Things were tight, but we did what we had to do,” Trammell says. “It taught us a strong work ethic.”

Trammell remembers hoeing weeds with her sister in the cotton fields. Their father would take the cotton to a gin in Kenefic and bring home the seed to feed his cattle in winter. She also recalls picking pecans up by hand. As the youngest in the family, she would stand with her gunny sack closest to the tree trunk. The line of pickers would extend out to her father, who used a cane pole to knock the pecans from the trees.

“We use all modern equipment now, but we didn’t use any kind of mechanization back then,” Trammell says. “It’s amazing how far technology has come.”

In 1993, Trammell went to work as an administrative assistant at Noble. At the time, the agricultural consultants purchased aerial images of land owned by producers with whom they were working. Part of Trammell’s job was to take those images and put them in a form that a consultant could use to measure land areas and make maps useful to the producer.

It would take at least two days, often a full week, to create one map. Then, in 1996, Trammell started learning software that used geographic information systems, or GIS, to take the handwork out of mapmaking. While the consultants today digitize most of the producer maps thanks to rapid advancements in programming, Trammell has her eye on other futuristic technology.

Maybe someday we’ll be able to fly a pecan orchard and count how many pecans are in the trees.”

Tresa Trammell

Most of her time now is spent flying drones across fields, gathering data for plant science research projects. She and others are also watching the evolving technology space for tools that hold potential for farmers and ranchers.

There are many tech upstarts coming out with suites of tools for producers, she says. Drones can be flown to count plants and detect diseases, weeds, pest problems and water stress. Research companies are testing the use of drones equipped with thermal imaging to identify feverish animals before they show symptoms of illness, which may help reduce use of antibiotics.

“These are all things we don’t know much about yet,” Trammell says, “but we know they’re coming.”

While most of the Noble Research Institute’s drone use is to gather information for scientists looking at how to develop more efficient, disease-resistant forages, Trammell says some of the data they collect is also used to help companies hone the algorithms of web-based apps and other tools for producers.

“Maybe someday we’ll be able to fly a pecan orchard and count how many pecans are in the trees,” says Trammell, who continues to help with her family’s pecan harvest every year.

Her father, now 82, still works from sunup to sundown alongside her brother, she says. They now manage 1,500 pecan trees and 140 cows on more than 3,000 acres.

“Looking back, I’m so thankful for what Mom and Dad did for us,” Trammell says. “There wasn’t anything given to us. We built it all on hard work, and we did it all as a family.”

Honoring the Past, Growing Stronger Together

Ronnie Peoples, construction maintenance technician, grew up on a farm in Mannsville, Oklahoma, where he continues to grow some of his own fruits and vegetables.

“My dad used to grow cotton, as did his dad. I remember stories of Dad telling about how he used to ride with my grandpa on the wagon loaded with cotton. In one story in particular, they had to stay overnight camping out in bitter cold weather. I also remember my mom making me a cotton sack, and I started pulling bolls with them when I was 3. In later years when I was growing up, we always had huge gardens or ‘truck patches,’ where my parents grew a variety of vegetables to sell and put up. As a youngster, I developed a distaste for shelling peas, snapping beans and cleaning corn; but we always had a cellar full of canned goods. My income as a youngster and teenager revolved around selling pecans, hoeing, selling blackberries, trapping, selling crawdads and hauling hay. I’ve grown a few fruit and pecan trees and vegetable gardens for myself. All of this plays a part of who I am of being independent but also having a connection to the agriculture community and learning to never give up; to always strive to do better; and to appreciate the outdoors, friends and family, as well as life and what our ancestors accomplished to bring us to where we are today.”

The Best Investment

Many of Josh Anderson’s childhood memories were made in a John Deere tractor.

From the time he could toddle, his grandfather would hold him while letting the young boy “steer” the tractor through peanut, corn and soybean fields. Later, as a teenager, he would drive solo, planting wheat and rye to feed cattle through the winter on their farm in Mannsville, Oklahoma.

By the end of elementary school, Anderson owned his first cow. She had come from his father’s herd, so, in exchange for pasture and feed, Anderson would give his father the bull calves while building his own herd through the heifers. One summer in high school, during baseball season, Anderson remembers checking a cow that was close to calving. He’d gone out to the pasture before a game and decided he’d stay home to make sure she didn’t have trouble.

“Life revolved around the farm,” Anderson says. “We were very family-oriented, and the farm was our job. It was all I knew.”

Shortly after Anderson graduated high school, the farm bill changed and his family could no longer afford to grow peanuts. In addition, the man from whom the family rented land died. Anderson’s grandfather retired and his father took an off-farm job, but Anderson was able to buy 240 acres of land they had previously rented so he could keep his cows.

“That focus on forage is good for the cattle producer. It’s exciting being a part of that because it means what I do here directly relates to what I do now on the farm.”

Josh Anderson

To make the loan payments, Anderson worked part time in the small grains breeding program at the Noble Research Institute while attending Murray State College. Seven years later, he returned to the organization after earning his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Arkansas. During his time away, he managed turfgrass — even spending a year tending the field at Fenway Park for the Boston Red Sox.

“I moved home intending to either work on the farm or at Noble,” says Anderson, who seized his chance to return to Noble’s small grains breeding program.

In the 12 years Anderson has worked, both part time and full time, with the program, it has released six different wheat, rye, oat and triticale varieties that emphasize forage production.

“That focus on forage is good for the cattle producer,” Anderson says. “It’s exciting being part of that because it means what I do here directly relates to what I do now on the farm.”

At home, Anderson manages 500 acres primarily for grazing cattle. He plants small grains he has helped develop as well as radishes, turnips and other species, which add diversity and boost soil health.

In 2017, he bought a no-till drill, which he says has been one of his best investments for both his land and his pocketbook.

“We don’t have to plow anymore,” Anderson says. “We’re only driving over a field once now instead of twice. That saves us fuel and time, which is a huge benefit especially when you also work off the farm.”

With no-till, Anderson now has more time and money to plant both pasture and field areas. His goal is to produce year-round forage for his cows, something Noble researchers have been evaluating. Following what they’ve found, he plants wheat and rye (which grow in cooler months) into his bermudagrass and native pastures (which grow in warmer months) so that there is nearly always something green. He also plants a summer cover crop for his cattle to graze so they don’t put as much pressure on the bermudagrass, allowing it to last longer into the fall.

As a result, Anderson doesn’t need as much hay to get his cattle through winter. While he used to feed 50 to 60 bales per year, he is down to 10.

“I’ve lived the good and the bad of farming and ranching,” Anderson says. “It makes all of what we do here seem a little more important.”

First-hand Experience

We combine our various backgrounds and expertise to find solutions to problems faced by farmers and ranchers.

Mike Trammell, senior plant breeder, grew up on a beef operation in Oklahoma before moving to Nebraska and working with cattle producers there. He now manages his own small herd in Wilson, Oklahoma.

“My experiences give me more of an appreciation for the decisions that producers make about the management of their operations when it is their sole source of income.”

Twain Butler, Ph.D. grew up on a beef and dairy cattle, hog, and wheat farm in Vashti, Texas. Today he leads Noble’s Forage Agronomy Laboratory.

“Growing up on a diversified livestock farm in the Southern Great Plains gives me an appreciation for what can help producers in this region.”

Charles Rohla, Ph.D., grew up raising beef cattle (stockers) and hogs and growing wheat and alfalfa on his family’s farm in Chester, Oklahoma. Today, he manages beef cattle, hogs, horses and pecans on his own farm in Roff, Oklahoma. He also manages Noble’s pecan and specialty agriculture activities.

“Having an operation helps me better understand what a producer deals with daily. This helps me understand what questions producers are asking so that we can help develop research projects that address those questions.“

Jim Johnson, soils and crops consultant, grew up working on corn and soybean farms in Illinois. He now manages a beef cattle and pecan operation in Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma.

“I know firsthand the weather, labor and financial struggles that a cattle producer faces and have firsthand experience with many of the practices I recommend on the job.”

Comments