Noble Land Stewardship Program Aims to Help Ranchers Put Numbers to the Value They Bring to Society

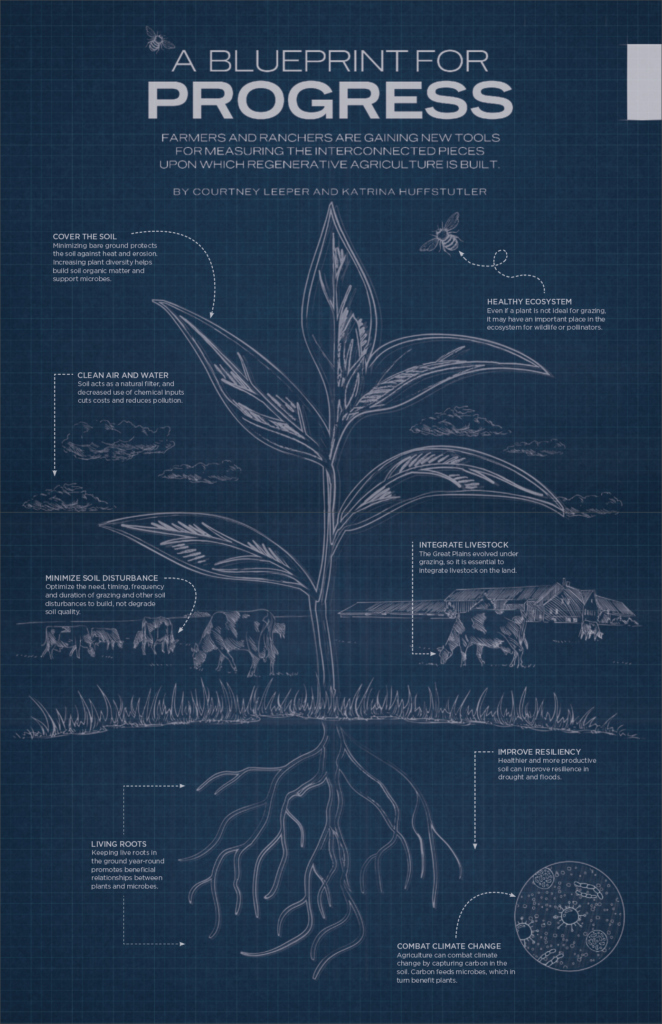

Farmers and ranchers gain new tools for measuring the interconnected pieces upon which regenerative agriculture is built through Noble Research Institute’s Land Stewardship Program.

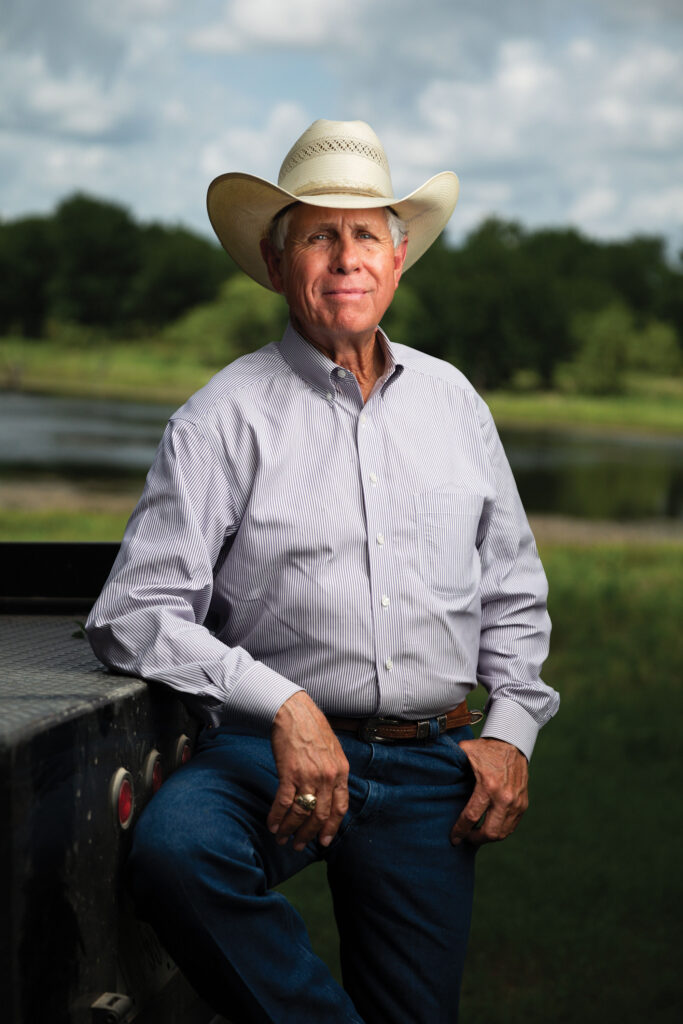

When asked about his cow-calf operation in Blooming Grove, Texas, Gary Price doesn’t open with the number of cows he runs or the breed he raises. Instead, he starts with the soil, describing the various types and combinations found on his ranch 50 miles south of Dallas.

It’s rather telling of where the cattleman’s priorities lie. He knows the importance of good stewardship because he’s seen the effects firsthand, and he’s not alone.

Regenerative Agriculture

Land stewardship is a journey that leads toward regenerative agriculture. It is not just about sustaining the land’s ability to provide for future generations but about improving that ability.

Regenerative agriculture is the process of restoring degraded soils using practices based on ecological principles.

Regenerative agriculture promotes:

- Building soil organic matter and biodiversity.

- Healthier and more productive soil that is drought- and flood-resilient.

- Decreased use of chemical inputs and subsequent pollution.

- Cleaner air and water.

- Enhanced wildlife habitat.

- Capturing carbon in the soil to combat climate change.

Rotation and Restoration

Price rotates two herds of cattle through about 45 different pastures on the 2,600 acres he has put together through the last 43 years. His intense rotational grazing plan is an effort to mimic what the bison did a couple hundred years ago. The bison would graze each piece of land for a short time and then move on, giving it a long period of rest.

“To watch the recovery is pretty amazing,” Price says. “Native grasses, if you continuously graze them … that’s how we lose them. They’re so palatable that cattle will graze those good plants down, and then you get the less desirable grasses.”

Between improving his grazing system, stocking conservatively and benefiting from evolving weather patterns, Price says he has been able to avoid feeding hay or buying supplements for eight years — an almost unheard of accomplishment.

Another one? He’s particularly proud to say a portion of his land has never been plowed, making it part of the less than 1% of tallgrass prairie that has not.

Cotton was king in his neck of the woods in the past. In fact, at the turn of the century, Ellis County had more cotton than any other county in the U.S. That means some of the acreage he has accumulated had been old cotton fields. He’s gone in and planted those in native grass.

“We’re passionate about what we do. We don’t consider it work. We just consider ourselves fortunate and blessed. But this is greater than that. We want to make sure we leave the land better than we found it.”

Gary Price, 77 Ranch, Texas

“We like to say our ranch has a mottled look,” Price says. “We’ve got some pristine prairie, but we’ve also got some in various stages of restoration.”

About 200 miles north, outside of Sulphur, Oklahoma, Susan Bergen’s ranch is on its own path to recovery. When she took over management of the family’s 12,000 acres seven years ago, it had not been profitable for decades.

Though the land had not been overstocked with cattle, the stocking rate was set on a per acre basis — 100 head in a 1,000-acre pasture — rather than through an intentional management plan. Bald spots, 240 acres worth, were left in areas the cattle had constantly used, and less desirable plants were taking over. The most desirable species — big bluestem, indiangrass, little bluestem and switchgrass — had been weakened.

6 Principles of Soil Health

1. Know Your Context

Farmers and ranchers must know their individual situation, including their climate, geography, resources, skills and goals.

2. Cover the soil.

Use plants to minimize bare ground and protect soil from erosion and heat.

3. Minimize soil disturbance.

Optimize the use of tillage, grazing, fire and other activities to build, not degrade soil.

4. Increase diversity.

Encourage different root systems to enable a diverse underground community.

5. Maintain continuous living plants/roots.

Promote positive relationships between soil microbes and plants.

6. Integrate livestock.

Foster the grass’s historical relationship with grazing and recycle nutrients.

At the recommendation of Hugh Aljoe, Noble Research Institute director of producer relations, Bergen took an inventory of her resources and began to work toward the goal of regenerating the prairie. She bought wheat, turnip, radish and Austrian winter pea seeds to no-till drill into both the bare ground and weakened pasture. Within three years, the previously “lizard licked” land was covered by a sea of green.

Bergen credits the mix with kick-starting the buildup of biology back into the soil, but she says her No. 1 tool has been grazing management. Her cattle are rotated under the guideline of “take half (of the forage), leave half.” They cross some pastures only twice per year, giving the land 300 days of rest.

The grazing, when used properly, actually spurs growth of the native grasses, something Cruz Guerrero, Bergen’s ranch manager, can attest to. Guerrero worked on the same land from 1998 to 2003 and says the quality of grass is much better now. Today, good stands of little bluestem, indiangrass and even big bluestem are reappearing across the ranch.

“This is important information for us to have. We are seeing the benefits of managing with the land’s long-term health in mind, but it’s important for us to be able to support what we’re doing with hard data.”

Susan Bergen, Bergen Ranch, Oklahoma

But when Bergen looks out over the range, she still sees what many would consider weeds. She has had to learn that even if a plant isn’t perfect for cattle, it might be beneficial to wildlife or pollinators. At the very least, it has roots, which means it is feeding the soil microbes.

“It took four years to have eyes to understand that,” Bergen says. “I understand now that every plant is an indicator of something going on in the soil and for the overall ecosystem. Sometimes I have to take a breath, step back and know that this is a journey. I have to focus on what’s right and keep learning and working to improve.”

Price and Bergen can see progress on their ranches, but the process takes time. And right now, there are no tools for producers to easily measure their ecological investment in the land or the value — beyond food and fiber — they provide to society. Jeff Goodwin, Noble conservation leader and pasture and range consultant, wants to change that.

The Quest to Quantify

Three cowboys look down at the ground where Goodwin crouches in the tall prairie grass on the Bergen ranch. With both hands, he drives a shovel into the earth and lifts upward, bringing forth fresh soil.

“You hear that?” Goodwin asks, following the crinkling of fibrous threads as they stretch then snap. “That’s the sound of roots. That’s a good thing.”

Goodwin explains the roots secrete sugars that feed the microbes in the soil, which in turn create an environment in which the best native grasses thrive. Especially the prized big bluestem, which is highly dependent on mycorrhizal fungi.

“Five years ago, this would have broken off into slabs,” Goodwin says, pointing to the deep brown soil as he crumbles it easily in one hand. Now, thanks to the life teeming within it, the soil is more porous. It can hold more water, giving the land greater resiliency in drought and a better chance at soaking up precipitation.

The soil also acts as a natural filter for water cycling from sky to stream to ocean. It provides home base for plants, which, with the help of their microscopic neighbors in the soil, pull carbon from the air and sequester it underground for food. Livestock, in addition to wildlife and pollinators, use the plants while returning nutrients to the soil and spreading seeds. Humans use what the land provides and, from the Noble perspective, are responsible for managing those resources in ways that keep these complex, interconnected pieces in balance.

What are mycorrhizal fungi?

“Mycorrhizal fungi grow within or alongside plant roots. The fungus forms a mutually beneficial relationship with the plant, which provides the fungus with food and nutrients. In return, the fungus helps the plant take in nutrients and water.”

Kelly Craven, Ph.D., former Associate Professor, Microbial Symbiology

“It takes a great deal of intentionality on the producer’s part to keep the system balanced,” Goodwin says. “It’s not just about applying practices. It’s about managing the entire operation with the land in mind.”

Right now, in general, farmers and ranchers are only able to go off observations and anecdotal evidence to determine the health of their land. As part of Noble’s Land Stewardship Program, Goodwin is working to provide producers with a process to quantify the value of managing land with a stewardship focus.

“We often say, ‘You can’t manage what you can’t measure,’” Goodwin says. “That’s the idea behind this program. We want to develop a science-based process for people to measure their land’s health so they can see their progress and share that story.”

Right now, the program is in a pilot testing phase with 12 ranches that stretch across almost 40,000 acres in Texas and Oklahoma. The land stewardship team has traveled ranch to ranch taking soil cores to a depth of 3 feet from more than 600 locations. They have also measured the vegetative metrics associated with those sampling locations.

Goodwin has measured available water holding capacity and is working to correlate that with remotely sensed satellite data like NDVI, a greenness index that can determine how green a field stays over time. Often, water, not nutrients, is the limiting factor that keeps a pasture from reaching its production potential, Goodwin says. Sometimes the land is just thirsty, even when there is no obvious drought.

The samples will be sent off to the laboratory. Once Goodwin receives the results, he’ll provide a report — what he calls the “baseline measurements” — to each rancher. In three to five years, new measurements will be taken and producers will be able to compare those against the baseline. Finally, the land managers will have numbers to back up the progress they have seen.

How Do You Measure Land Health?

One goal of the Land Stewardship Program pilot is to determine which metrics are the most valuable in indicating to producers how they are doing in keeping the ecosystem they manage in a healthy balance.

Soil Samples

89 total measurements from 5 tests that indicate:

- Water storage capacity

- Soil organic carbon

- Soil texture

- Type and amount of

- biological organisms present

- Nutrient levels

- Overall soil health

Vegetative samples

9 total measurements that indicate:

- Percentage of bare ground

- Height of plant canopy

- Plant biodiversity

- Forage production

- Soil’s ability to take in water and resist erosion

Pilot producers are also testing MaiaGrazing software, developed by an Australian-based company. The unique platform provides forage and grazing forecasting analytics, which helps a producer make stocking rate decisions. Learn more about MaiaGrazing at maiagrazing.com.

What Matter Most

Goodwin hopes that what he learns in the pilot will have application for producers nationwide. One goal of the project is to take all of the data and figure out which metrics tell a person the most about his or her land. This way producers don’t have to spend the time or money needed to test for information that isn’t as helpful.

Once the top metrics are identified, tools can be honed to make it easier for an individual on any soil type, in any part of the world, to take that measurement.

For example, Goodwin is working with Yale University to test a hand-held device that measures soil organic carbon. Such a tool could allow a producer to simply scan soil in the field rather than send it off to a laboratory. But does the device work? To find out, the team used it to measure soil organic carbon in all of the soil samples Goodwin collected, which he also sent off for testing. They’ll compare the laboratory results to those from the new technology. This will enable them to give confidence ratings on how well the device works on different soil types.

Goodwin says developing ecological baselines will give producers a way to prove to themselves and others that their efforts are truly benefiting the land and, in effect, all of society.

For the Benefit of Us All

“When people talk about agriculture’s impact on the environment, they talk about how cows emit methane. But how much carbon is sequestered in the ground by plants — including the grasses those cows live on? The Land Stewardship Program gives us the opportunity to have someone come out and measure carbon sequestration on our property and then again in five years. We’ll get a better idea of our true impact, which is important to me because I want to be sure I’m doing things that are going to benefit my son and all of us.”

Meredith Ellis, G Bar C Ranch, Texas

In addition to giving producers site-specific, real-time information upon which they can tailor goals and make decisions, the program could eventually set them up to participate in marketplaces designed to pay them for their ecosystem services, like carbon sequestration.

It was important to create a program that works in real life, Goodwin says. That’s why they brought in pilot producers like Bergen and Price.

“I think the world of Noble and their credibility and integrity that shows in everything they do,” Price says. “It’s so important to find those producers who are doing some good management practices on their land and tell their stories to show it can work.”

While Land Stewardship Program participants follow science-based best practices based on land stewardship and soil health principles that lead to regenerative agriculture, Goodwin and the producers recognize that land stewardship is not one-size-fits-all.

“We understand every ranch has a unique set of assets to manage and challenges to overcome,” Goodwin says. “But there are fundamental principles that apply no matter the operation. Good stewardship is universal, and we’re going to be able to measure it soon.”

Comment