The Whys, Wills, and What Ifs of Regenerative Ranching

The ranch life is full of unknowns, but is there a path to finding the answers? Three ranchers share their journeys with the questions. And one research project seeks the answers.

Mountain View is a town you don’t find by accident. It’s 40 minutes south of the beaten path.

You’ll eventually run into it, but only after traversing miles of relaxed slopes, patchy grass, lonely fences and a rolling silence you might experience if floating in space.

Eventually, the rhythmic ups and downs of the road make you forget you’re expecting a town to pop into view any minute. The quiet is so absolute, the landscape so clean, the peace so inviting, you may find yourself content even if the road goes on forever.

Then Mountain View arrives like a desert mirage. It’s the most neighborly smile the sparsely populated land has to offer. It’s just there. Just resting. Just waiting to be found.

There’s nothing flashy or unconventional in Mountain View, Oklahoma, unless you count Rick’s Custom Cycles, a Harley-only repair shop attracting hog enthusiasts from three states to visit the deep, dark bowels of the aging brick building.

The tallest structure in Mountain View is the grain elevator, which at a distance resembles a launch pad readying a rocket. In front, more times than not, a green John Deere tractor or two rests in the shade.

At the single stop sign in Mountain View, turning right leads you to Dollar General or Flowers by Charlene, where locals drink their morning coffee around a table littered with silk flowers that didn’t make the cut.

If you need to refuel or make a deposit, turn left.

When lunchtime arrives, you can choose sandwiches and pizza at the Hop & Sack convenience store or sandwiches and pizza at the E-Z Out Drive-Thru with a side of its specialty: a 54-cent cup of ice. On Sunday, you can park in one spot and choose between the United Methodist Church or the Church of Christ, both immaculately situated as next-door neighbors.

The town is still living and dying. Sweet Treats, a new specialty snow cone shop, opened in May. The Little Washhouse and A Little Of This And That stores closed long enough for thick dust to coat the windows. Local youth now use it as a message board to their current loves.

This is small-town life. This is Mountain View.

It’s a quaint town in flyover country. One of many thousands of small towns dotted across rural America, easy to dismiss because few know they exist. Yet, it’s in these tucked-away places that a revolution in agriculture is ongoing.

Farmers and ranchers outside towns just like Mountain View are taking on the biggest challenges in the worldwide agriculture sector and are willing to ask seemingly unanswerable questions, like how to keep their ranch profitable, how to build soil health while decreasing inputs, how to produce the best-tasting beef in the business, and how to make the ranching way of life give back more than it demands.

One of these pioneering ranchers lives 10 miles outside Mountain View in the shadow of the Wichita Mountains. Many know him as simply “the chicken man.”

In His Element

Regenerative rancher and entrepreneur Brett Peshek raises hens, hogs, sheep and cattle on pasture at his ranch near Mountain View, Oklahoma. He sells thousands of hens plus meat products through his company, Element Foods.

Healthy Ecosystem: What if this doesn’t work?

Brett Peshek has one of those quick, easy laughs that sounds like he’s being tickled. He throws one in between deep ruminations about ranching and the future of agriculture. One minute he’s talking about the importance of succession, the next he breaks out in a “hehehe” laugh that makes you laugh, too.

“People call me up and say, ‘Hey, I hear that you’re the chicken man. Can I buy 100 chickens?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah. I don’t care. Call me whatever you want,’” says Brett, sporting a stylish-without-meaning-to-bestylish golden-blond beard and curious blue eyes. “You have to have a thick skin a little bit, but the more that people talk about you, whether it’s good or bad, the more marketing you get for free.”

Hehehe.

He started his chicken business with an initial sale of 500 fully mature hens. By next year, he plans to hit 8,000. If his history is any indicator, he’ll exceed that number.

“I found it so sad that people were driving three hours away to buy chickens so they could raise their own eggs,” he explains. “They can buy chicks from the store, but the problem is they have six months of time and no equipment to raise them before that chicken is actively laying eggs.”

Brett saw the need. And filled it.

When he has chickens to sell, he notifies interested parties through Facebook, while getting around the social media site’s animal sale limits by butchering the spelling from “chicken” to “chikun,” “for” to “fur,” or “sale” to “cell” like “some backwoods hillbilly farmer,” Brett says, and people love it. They laugh. Then they buy his chickens.

Hehehe.

This is only one of several income streams he’s working under the umbrella of Element Foods. Brett isn’t doing only one thing to get his products noticed or to lower his expenses or to enrich his soil. He’s doing everything he can think of. He looks at ranching with a mind toward entrepreneurship that has him raising pigs and sheep, tossing in cattle and moving truckloads of hens. If those products don’t bring in the money, he’ll try something else.

That’s the same way he approaches his soil, too.

On his 640-acre ranch outside Mountain View, this native Nebraska man tests until he finds what works, then repeats and adapts. What has worked, so far, includes adaptive grazing management, minimal chemical inputs and a continual focus on the health of his soil.

Part of his method to building the soil comes through his consistent Haney soil tests and phospholipid fatty acids analysis, along with the all-toocommon method of trial and error. One example of trial but not necessarily error was when he attempted to build more residue by planting buckwheat. The buckwheat failed, but he succeeded in getting earthworm castings into the soil.

“I try to find a reasonable economic experiment for my farm that I do each year,” Brett says, while debating whether the next test will be about mycorrhizal fungi and what would happen if combined with compost tea or earthworm castings.

His other method of determining what works on his ranch is simply walking it and using that insatiable curiosity to spot new forages, insects or pollinators, sure signs nature approves of his management.

“There’s some golden prairie clover,” he says, while ignoring the glaring 99-degree afternoon heat overhead. He takes a moment to admire the perennial and find its purple cousin. When he comes across a velvetleaf gaura, he stands and pets it while speaking gently, as if it’s listening. “I don’t consider anything invasive. There’s uses for all species at different times of the year.”

Horny toads are also returning to his fields, along with elusive quail he’s always stopping to hear.

“There they are. You hear that?”

Not really.

He mimics the chirping, whistling combo. “It sounds like that.” He mimics again, and a chirp/whistle responds.

“That’s the quail.”

Hehehe.

Everything he tries, every test, every new endeavor, is in the search to answer the biggest question that plagues his every working day.

“The biggest challenge for farmer or rancher is the ‘what if.’ What if it doesn’t rain? What if it hails? What if … There’s going to be those events every year, but you have to look at those negative events positively. It’s like, well, I see this species showed up this year because of that hailstorm, or we had to feed hay to generate income, so now this spot is fertilized now. The ‘what if’ is about getting your mindset right,” he says. “The climate is one major challenge we face, but the climate’s going to do what the climate’s going to do. And you can only control so much of that by what lands on your farm and how you manage that rainfall or sunlight.”

The biggest challenge for farmer or rancher is the ‘what if.’ What if it doesn’t rain? What if it hails? What if…. there’s going to be those events every year, but you have to look at those negative events positively.”

Brett Peshek

For Brett, the unknowns are a way of life. He wouldn’t mind having more answers than questions, but how to find them?

Across the state, 255 miles east and further south than Brett, at the very edge of what remains of Oklahoma before becoming Texas, is another rancher asking questions, too. And the answers have come at a price.

Multitasking to the max

Justin and Jenny Dow with their son, twin daughters and twin sons in the combination cover-crops pasture/milpa garden on their ranch at Valliant, Oklahoma.

Financial Prosperity: Why do it that way?

Justin Dow stands in his living room with an Olaf toy from Disney’s “Frozen” looking dumbfounded near his foot. Justin is tall and agile, which served him well during his college bull-riding days. Now, it helps him read messages from the International Paper mill, his day job as safety manager, on his phone with his left hand and balance 1-year-old Watson with his right.

Behind him is the family’s home-school classroom with “Sesame Street” books scattered around the room next to a clean chalkboard, the game Operation and oldschool seating with attached tables. His wife, Jenny, is the teacher. She wears dark glasses on her oval face and has the look of a superhero alter ego. She’s already taught their 7-year-old son, Logan, how to write in cursive and is working on doing the same for their twin 4-year-old daughters, Maddison and McKinley, before they turn 5.

Both girls are dressed in their Sunday best. McKinley hides behind her own arm while Maddison explains that her “church dress” has three colors – “pink, light pink and dark pink.” It’s a pretty dress.

This is the Dows’ world. It’s their home, their business, nearly their undoing and definitely their future. It’s doing a lot for a neatly built, two-story gray rock home situated pristinely on their ranch in Valliant, 80 miles outside of Durant, Oklahoma.

With the simple command of “switch,” Jenny swaps Watson for his twin brother Wyatt, plops down on the couch, tosses her waist-length brown hair over her shoulder, and nurses the second twin. Nap time approaches.

This is the juggling act that goes on 24/7, 365 days a year with the Dows. When she’s not teaching and caring for their five children or running her dog-breeding business, she’s managing the ranch. When he’s not keeping 700 employees safe inside the paper mill, he’s laboring on their ranch. When was the last time they were alone together?

“We got out on a side-by-side night before last. We had some hay laying down, and she wanted to see it before it got cut,” Justin says.

Jenny, the natural storyteller of the two, gave the details. “I left my 7-year-old to watch my 4-year-olds and my 1-year-olds. And we timed 10 minutes. I said, ‘Okay, you have 10 minutes on the clock. Let’s go.’”

The assumed slower-paced life of the ag entrepreneur, in reality, is moving at breakneck speeds for the Dows. If Jenny didn’t tell you, you’d never know she spent the night up every hour with the boys – they’re teething – but still managed to get everyone ready for the day’s appointments. And Justin, breathlessly managing work and family life, always makes it to family dinner after getting home each day, but then leaves again for his evening chores.

These are the sacrifices the Dows are making for the life they want as ranchers. It’s the life that holds no disillusionments now. Being successful financially in ranching is tough. Sometimes it feels impossible. In 2015, they learned this firsthand.

It was early in their marriage that Justin and Jenny decided to expand. They had roughly 640 acres leased for their small herd and a desire to switch to Red Angus. With the purchase of 46 certified, threein-ones, they were on their way.

“We paid top money for those cattle,” Justin says.

“We paid stupid money for those cattle,” Jenny adds.

On what Jenny calls “napkin math,” it made sense. They purchased the cows for so much. They’d produce. Their calves would bring so much. The math worked out. On a napkin. In real life, nothing went according to plan.

Out of the 46 cows, only two bred.

“Talk about financial hardship,” Jenny says. “When it happened, I stood there crying silent tears.”

This young family who grew up rodeoing and working cattle and dreaming of having a thriving ranch of their own were now looking at absolute ruin. No crop. No cash. Seemingly, no way through.

“What do you do?” Jenny recalls them asking.

Yes, what?

“Well, you just fight,” Justin says.

“Things got pretty bad. I got the vets involved. I started working with our county extension agent through Oklahoma State University. At that point, it was more about asking questions. What caused this? Until we knew what caused it, we didn’t know how to fix it.”

The concept of put-cow-bull-together-get-calf went out the window. There was more to it than that. Even though Justin and Jenny had both been raised around cattle, there was still more to learn.

“Most of the things that went right for us up to that point were luck and just osmosis,” Justin says. “You see things happen. You do it that way. That’s the result. You just expect that to be the case, right? But you don’t understand all the variables that affect it.”

Justin and Jenny got to work learning those variables.

“One of our strongest traits is we’re problem-solvers. We like to work the puzzle and figure out how to solve it,” Jenny says.

One of our strongest traits is we’re problem solvers. We like to work the puzzle and figure out how to solve it.”

Jenny Dow

Realizing their cows were in a weakened body condition when they tried the initial breeding, the Dows then changed their focus from breeding to building health. The bulls were pulled, and the cows were deliberately fed for strength-building. When December 2015 rolled around, their bodies were strong, healthy and ready for a second attempt. Using artificial insemination to support their bull power, the Dows tried again. This time, the breeding succeeded.

Instead of simply taking the win and moving on, Jenny says they asked “why.”

“We got very inquisitive. We started learning,” Justin said. “Up to that point, we had cows because we had cows. It was what we wanted to do, and we thought we knew what we were doing. Clearly…” Justin opens his hands in an ‘obviously we didn’t’ gesture.

Their curiosity meant driving the vets and extension agent crazy with questions, Jenny says. But they kept asking. Eventually, they learned those 46 threein-ones that offered so much initial promise were teething, much like her twin boys right now, and physically run-down. That is why the most notorious time for young cows not to breed, she explains, is with the second calf.

Now they understood why they lost money, but they still had to find a way to recover. Napkin math wasn’t going to cut it anymore.

“We had to start thinking about finances at that point,” Justin says. “Most people in agriculture are not business-minded people. They’re production-minded people. You’re in agriculture because it’s a lifestyle. You grew up that way. It’s just what you do. You like doing the tasks. You like being around the livestock. But you aren’t businesspeople.”

Jenny says there’s even pride in that fact. “It’s like ‘I don’t work behind a desk. I’m in agriculture.’ And that’s true. But it’s a business as much as anything else.”

She understands that sense of accomplishment and love of the always dirty, often gritty, sometimes miserable, but always rewarding physical work on the ranch. Up until her second set of twins, she did 80% of the tending, feeding and checking on cattle herself, Justin says. She’d load Logan, 3 at the time, and the girls, still infants, and pack them in the feed truck like sardines. Logan was taught how to operate the emergency lights. When his sisters woke up from their nap, he’d set off the lights so that Mom, working the cattle just outside, saw the signal and came.

It worked. And it taught Logan how to do “big brother” well, like keeping his brothers from gnawing on anything they can wrap their fingers around, like raw okra, when crawling through the diverse crop mix of their family’s milpa garden.

For the Dows, ranch work has always been their life, but they needed to view it differently now. It had to be profitable, too. They were in a hole and, somehow, some way, had to dig out.

“We could have given up, but that wasn’t an option we considered,” says Justin.

While they learned about cattle nutrition and reproductive cycles, Justin also reached out to an area economist to help map out a business plan.

“I’ll never forget this. When he first sat down with us and ran the numbers, he said, ‘You’re going broke.’ We were offended by that,” Justin says.

Jenny, the more demonstrably passionate of the two, agrees. “I was very offended.”

The Dows made changes. They moved toward making their ranch as sustainable as possible. That meant trying rotational, high-intensity grazing that allowed them to run more cows and have a better supply of grass. It also meant cutting the cost of spraying because weeds were managed through grazing.

The sound of that rotation often overwhelms even the lively chatter inside the house, like it does now.

“They’re moving cows,” Jenny explains about the noise, nodding her head toward the scene from “Rawhide” just beyond the yard. “We have an alley right there, and it goes to the other side of the road. So, he (the ranch hand) is moving cows from that side of the road to just right by my house.”

Outside, the moans and moos of the livestock join with the inside chatter of Wyatt, now awake from his nap and talking all about, well, no one knows what. His quieter brother, meanwhile, is busy dragging one adult-sized shoe across the floor to, well, no one knows where.

Jenny smiles as the cows pass by. “We enjoy it.”

They must. Love is required to keep going and to find a way past the questions to the answers, even if tentative or temporary. So far, it’s working. The business that started with 35 head on 320 acres of leased land and was managed by a mom and her infants is now roughly 450 head on 1,238 acres of owned land and managed by the Dows and their staff.

How did they keep going?

Justin says by setting up different enterprises, like their cow-calf enterprise, stocker enterprise and custom beef enterprise. And by “squeezing all the juice out of the fruit, if you will.”

“The last couple of years have been super tough,” Justin admits. “To say, ‘Oh, well, you did it and it worked?’ I wouldn’t say that. I would say every single day is extremely stressful. ‘Things are still going to work, right, Honey?’”

Jenny smiles.

Another rancher, stewarding the tenacious soil in the northern Oklahoma plains, has confronted the mental stress of ranching life by combining brotherly love with breakfast food. It’s a tasty solution.

All In With No-Till

Tom Cannon, CEO of The Goodson Ranch at Blackwell, Oklahoma, examines the blooms on a cotton plant growing on his ranch. Crop residue protects rich soil at his feet, the result of 25 years of no-till cropping.

Personal Wellness: Will I be here next year?

Tom Cannon has been ordering two eggs over-medium with bacon (sometimes crisp, sometimes he wants a variety) at Mary’s Grill in Tonkawa for four years. The other four men at his breakfast table usually opt for something different. Bryan prefers Carol’s Scrambler, a local specialty of scrambled eggs with spinach and tomatoes. Marty orders French toast. Joe usually goes for something sweet like a waffle. And Gary is the mystery man. No one can ever guess what he’s going to order, except maybe Lori, their waitress.

The five farmers sit in the east room, per their usual, and the group therapy begins.

Everyone brings their rain reports and their problems. Whoever got the most rain, pays. Whoever has an overwhelming problem, gets support. Through the years, the issues addressed around a plate of breakfast food have been thicker than the sausage gravy. This isn’t the water cooler. This is the priest’s confessional and the therapist’s couch. They’ve worked through problems together ranging from divorce and alcoholism to depression and hopelessness.

The only thing demanded at this breakfast, other than coffee refills, is openness.

Initially, when the group started gathering for breakfast in 2018, it was to discuss good production practices. It didn’t stay that way for long.

“By our third meeting, it was ‘how’s your family, how are you doing, are you holding up under the stress?’ It was all a support group,” says Tom, who describes the comradery as similar to firefighters in a firehouse.

But firefighters are experiencing trauma bonding.

“Exactly,” says Tom, flashing a knowing yet still-boyish smile.

He tells the story of his breakfast buddies while relaxing out of the heat inside his “barndominium,” an eye-catching two-story structure next to his home in Blackwell, Oklahoma. The adult playhouse offers a full kitchen, two private bedrooms and private baths, and enough comfortable seating to enchant the most energetic visitor to sit a spell and relax. It’s also a favorite spot for Buddy, his son’s border collie, who uses his soulful Betty Davis eyes to threaten dogs and charm people.

Part retreat, part escape, the barndominium is a place for the family to recoup on hard days and for friends to claim on traveling nights. It’s built, from the outside padded porch swings to the upstairs sprawling couches, for social interaction. For togetherness. For community.

Furry trophies hold their proud heads along the walls, while scripture verses like Joshua 24:15 bring direction and purpose. To seal the deal, a handwritten message of “Smile, Jesus (heart)s you” is scribbled on the whiteboard.

For today, it’s the most popular spot on the ranch because it’s cooler than the 102-degree day outside. Tom sits at the dining table with two of his children — Jacob and Reagan — flanking him on either side. The dining chairs might be the hardest seats in the place, but the table positions the trail mixes — one sweet, one spicy — within reach, so everyone agrees to sit up straight for a while.

Behind Tom, just over his shoulder, is a window that looks out on the acreage in front of his home. That’s the spot where he first learned to till at age 8. Ranching, for him, started early and was inevitable. The Goodson Ranch in Blackwell has been a ranching staple in Oklahoma since the 1893 Land Run. Four generations later, Tom stepped in as CEO.

Even though it was a family tradition, that wasn’t his initial plan. In 1997, while Tom was attending college to be a microbiologist, his father suffered a debilitating pickup wreck on his way to an auction in Pratt, Kansas. Tom’s future instantly changed.

His family and its 4,000-acre ranch needed him. Tom would need to run Goodson Ranch, but that didn’t mean he had to run it the same way.

“I came back to a failing system,” says Tom, remembering what he faced when stepping into his new role all those years ago. “The system had been good for a long time, but it wasn’t working anymore. Times changed, and our farm had to change.”

Seeking answers, Tom signed up for the “No-till on the Plains” conference and the accompanying bus tour to the Dakota Lakes Research Farm in South Dakota with Dwayne Beck. It turned out to be a historic moment in regenerative ranching and a historic moment in Tom’s life. On the bus with him were men who would become the pioneers in the practice of no-till, men like Dan Gillespie, Ray Ward and Paul Jasa.

“God placed me in this seat where I had Beck, Gillespie and Jasa all around me. We talked, and I just got goosebumps thinking about it because it was so divine,” says Tom, rubbing his arms. “I came back and said, ‘Dad, we’ve got to sell everything because I can’t afford to upgrade any of our equipment. So, we have to sell everything and buy a no-till drill. One drill. That’s all I want.’”

The Goodson Ranch now had a new legacy. Not only would it be designated an Oklahoma Centennial Ranch by 1999, it would also become an area leader in regenerative principles in action.

All with one drill, about which Tom said he “lived in that thing,” he covered 10,000 acres per year. For years. But it paid off. Within his first three years of making the change, his wheat yields doubled. Twenty years later, the acreage had more than doubled.

Back then, these no-till guiding principles weren’t called “regenerative.” They were called “the right thing,” he says. “I called it ‘I-just-want-to-try-to-grow-commodity-crops-in-the-same-way-that-thenative-grass-in-my-area-is-growing.’ I was just mimicking creation in my area.”

He used 30 acres of his 3,000 native grassland acres in the tallgrass prairie on the edge of the Flint Hills to test different food plots and grasses at different times to see what worked and what didn’t. It also didn’t hurt that no one could see what he was trying and judge him if it failed, his son Jacob teased.

“It was incredible what you could do on soils that had never been broke. You’d go in and direct-seed stuff and just see what happens,” says Tom, again with the boyish smile. “You can learn a lot from that. I saw things grow in different ways and saw some things that were very surprising.”

One year, he tried a small crop of milo with zero commercial fertilizer and zero tillage. The results were shocking. In fact, the results were so shocking Tom took his milo seed dealer up there to see for himself. The milo seed dealer was also shocked. Tom had grown the best milo crop in the area. A few years later, his milo seed dealer went 100% no-till, too.

“We’ve been no-till for,” Tom pauses to count in his head, “this will be 25 years.”

That’s a lot of unknowns to have lived through and survived. Out of all the ways he’s managed success this long, one lesson stands out the most.

“If I’ve learned anything, it is how important it is to network with other producers who are like-minded. Anybody wanting to change their operation into a more sustainable operation, No. 1 is network with those that have gone before you,” he says, while stopping momentarily to place a quick call to a rancher on the verge of quitting. He knows of three retiring this year alone.

If I’ve learned anything, it is how important it is to network with other producers who are like-minded.”

Tom Cannon

It’s this outreach, and the support from men like his breakfast buddies, that get him through the hard years. Hard years like 2022.

“We all knew we had the potential for this year to be the makeup year of all makeup years,” says Tom, explaining how, if anyone in farming would pull in $2-$3 million in a year, this was that year. “And it hasn’t happened because of the lack of rainfall and high heat.”

The high hopes of this year have been met with harsh disappointment. It’s these waves of possible feast and ultimate famine that make support groups, check-up calls and the farming community all the more important. But it doesn’t stop there. He says, ultimately, it’s believing in a power, a loving power, greater than himself.

“It takes a huge amount of belief that the Lord’s got your back,” says Tom. “You know that the Holy Spirit is going to guide you in your decision-making and that, eventually, all of that works together for good.”

That’s where his breakfast buddies go for guidance, too. They share a Bible verse at the beginning of every meeting and pray together when all their many different food orders arrive. It’s also where Tom is seeking the biggest question for himself, “Will I still be the manager and steward of this land next year?”

He says that answer is going to require divine intervention.

Gathering Data: How do you find the answers?

Outside towns like Mountain View, Valliant and Blackwell, on land you wouldn’t notice passing outside your window if the road took you past it at all, is where the land stewards and food providers of the nation are testing new ideas. The state of the soil and the future of the industry demands it. And, yet, the path toward a healthier overall ecosystem, financially prosperous ranches and a lifestyle of flexibility is riddled with constant questions.

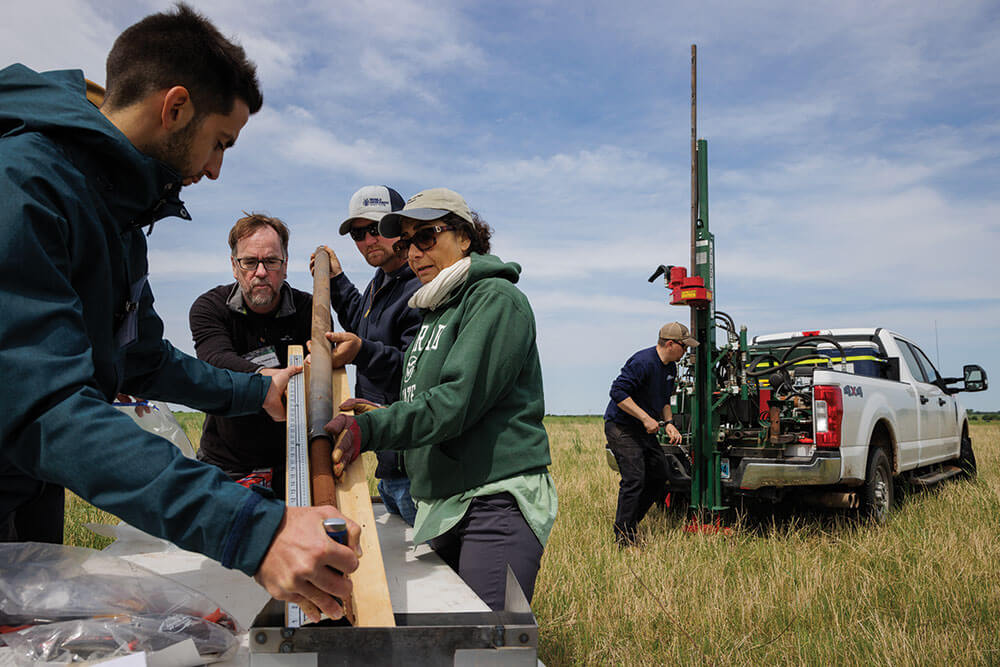

It’s those questions that have brought together researchers from 11 nonprofit and private organizations, along with public universities, all specializing in environmental and behavioral science, to unite in one mother-of-all studies. Metrics, Management, and Monitoring: An Investigation of Pasture and Rangeland Soil Health and Its Drivers, called the 3M project for short because even the name is intense, is the most comprehensive study of its kind. It’s a $19 million game-changer kind of study. The kind that has the potential to impact government policy and turn some of the unanswerable questions into statements and struggling ranches into financially thriving operations.

“It’s the ‘hold my beer’ of all studies for grazing,” says Jason Rowntree, a researcher at Michigan State University and co-project director for the 3M project. “I’m joking, but it is. We are doing intensive metrics and analysis of grazing management all across the United States.”

The “all across the United States” description isn’t hyperbole. The study gathers precise metrics on the amount of carbon in the soil, on the water cycle, on the life and growth and evolution of the ecosystems on 60 ranches in Michigan, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas and Oklahoma.

“I am not aware of any study at this scale, from the Michigan pastures to the diverse rangelands in Oklahoma and the short-grass prairies of Wyoming; adopting the variety and integration of field measurements; literally following carbon, nitrogen and water as they cycle from up into the atmosphere to 1 meter deep into the soil passing through plant and livestock, and coupling this intense field monitoring work with advanced ecosystem modeling through state-of-the-art data fusion; and with socio-economic analyses,” says Francesca Cotrufo, a researcher at the department of crop and soil sciences at Colorado State University and a co-director of the project.

It’s the breadth and depth of the study that will provide these 60 participating ranchers, as well as the agricultural community at large, with data to help create informed decisions on the best, most adaptable, most profitable soil management practices.

“The engagement is not just a simple survey or education program,” says Isabella Maciel, a systems researcher at Noble Research Institute and co-director on the 3M project. “We scale up our in-depth metrics. Then we use this information to create the most advanced modeling for soil health and carbon sequestration, water cycling, forage growth and other metrics.”

The comprehensiveness of the study not only extends into the raw soil metrics, but it also addresses the overall well-being of a ranch and ranch family and seeks answers to so many of the questions ranchers pose: How can they make their ranch more profitable? How can it be managed to give them more time? A freer lifestyle? A moment to rest and, like the Dows, have more than 10 minutes on a side-byside together? Or, like Brett Peshek, offer guidelines that can direct his testing and data collection on his ranch? Or, like Tom Cannon, encourage him and his fellow ranchers to keep going?

“I’m a big data person. I appreciate data, but it can be dangerous, too, when it’s out of context. It can give people false hope,” says Brett. “You have 365 variables in a year. So, data has to be based on adaptability and what that farm’s doing. It’s not necessarily what that exact farm is doing, but how they are doing it.”

Taking into account those variables is why the 3M study will be a five-year-long gathering of data using the most precise, exhaustive techniques to date. In the end, the researchers hope to find real-world solutions and offer answers to the consistent unknowns in ranching.

“Ranch management often boils down to opportunity costs, whether to hay or graze, sell or retain, destock or grow,” Isabella says. “In the future, when ranchers will be paid for the natural capital their landscapes are producing, another set of ‘what ifs’ will evolve, ones that say ‘Do we get more aggressive with stocking rates and grazing intensity, or do we make decisions that work to build more soil carbon, water retention or other metrics? Do we fertilize or not?’ But ‘what if’ we can identify management that gives the best of both worlds? What if the decisions ranchers make that add resilience are the same decisions that also increase profitability due to resilience? That is in a nutshell what we hope to get to, providing information on management and how it is impacting these important trade-offs ranchers face every day.”

Those are the questions. Now begins the hunt for answers.

Comment