Resilient: How Healthy Soil Provides Ranchers a Secure Foundation

In the end, it is only when both rancher and soil are healthy that they become resilient.

The year 2020 left an indelible mark on humanity. A global pandemic brought disruption and lockdowns. Isolation led to uncertainty and fear. And — for a moment — the world held its breath.

Then courage took hold. Heroes emerged. Innovation blossomed. Society adapted. Generosity became the battle cry. And tragedy gave way to resolve.

Countless stories of selflessness arose from this year of adversity. Doctors and nurses waded into a viral ocean to offer safe harbor to their patients. Teenagers delivered food to their elderly neighbors. Grocery stockers filled shelves for minimum wage. And — in a year when society reawakened to its fundamental dependence on food — farmers and ranchers continued to fuel the supply chain.

For those on the regenerative ranching journey, seasons of strife are more readily endured because their operations are built on the bedrock of healthy soil.

Story after story demonstrates that nourishing the soil does more than just impact what is below the ground. It creates a ripple effect that benefits the plants that grow in the soil, the animals that eat those plants, the quality of the water that runs across that land and ultimately the society that depends on it all. Healthy soils then have more resolve, and more resolve was necessary this year.

This annual report illustrates the regenerative pilgrimage through the experiences of three farm and ranch families, examining 2020 not through the lens of a pandemic but through the optics of soil rejuvenation and profitable food production. These narratives demonstrate how intricately connected humanity is to the microscopic universe beneath its feet. This mutually beneficial relationship must be stewarded.

If guardians of the land invest in the health of the soil, it will, in turn, bring forth a secure foundation for the farmer and rancher. Because, in the end, it is only when both rancher and soil are healthy that they become RESILIENT.

What is Regenerative Ranching?

To truly understand regenerative ranching, one must understand what it is not. It is not a formula, a universal how-to manual or a one-size-fits-all recipe. It’s a mindset.

Regenerative ranchers seek to nurture the land’s natural abilities to restore the soil using practices based on ecological principles (discussed later in this annual report). The regenerative rancher thinks of soil, plant, animal, air, water and themselves as part of one interconnected system that serves as the foundation for their operation and society. Every decision, then, considers the whole enterprise — not just the individual pieces.

In regenerative ranching, context is king. Applying the ecological principles will be different at every location. What a producer in California needs will be drastically different than one in Texas. Likewise, how the principles are applied at one ranch could be different than at the farm on the other side of the fence.

But the results are remarkable.

Regenerative ranching ultimately builds soil organic matter and makes the land RESILIENT. Healthy soil is more drought- and flood-tolerant. It also results in cleaner air and water, and captures carbon to combat climate variability for the benefit of all society.

Despite all the benefits, one question rises to the top of every rancher’s mind: Can I still be profitable? It’s a question that must concern all of society.

Regenerative Agriculture Defined

Regenerative agriculture is the process of restoring degraded soils using practices based on ecological principles. Regenerative ranching applies those practices to grazing lands and promotes:

- Building soil organic matter and biodiversity.

- Healthier and more productive soil that is drought- and flood-resilient.

- Decreased use of chemical inputs and subsequent pollution.

- Cleaner air and water.

- Enhanced wildlife habitat.

- Capturing carbon in the soil to combat climate variability.

Learn more about regenerative ranching at www.noble.org.

The Rewards of Rejuvenation

Applying regenerative principles to management decisions does not mean sacrificing profits.

For many, the need to be more profitable is what brought them to regenerative ranching. Healthier soil is able to do what a farmer or rancher needs it to do without as many inputs — which saves time and resources.

It enables the land to grow forages and animals, and it also encourages agricultural producers to think beyond the typical to find new enterprises that help them make the most of their resources — and capture more profit.

In other words, regenerative ranching is about managing the land in a way that rejuvenates its natural abilities. It boosts its natural fertility by — and here’s the key — working with the cycles of nature, not outside or against them. It is less focused on boosting yields and more concerned about working within the available resources, making the most of what is there and reinvesting in its longevity.

This is how regenerative agricultural producers become RESILIENT producers, strong and flexible enough to handle any outside pressures.

In short, regenerative agriculture is a path to profitability today and ensures that farmers and ranchers leave a legacy for tomorrow. And ensuring the land remains stewarded is good for all of society.

The No. 1 challenge is always going to be change.

Michael Vance

Anytime there’s change, there’s a learning curve. Different is sometimes scary, but you’ve got to look at the big picture. We have to decide when to change and when not to change. Regenerative agriculture is not an easy step-by-step approach. It’s about you as an artist taking the resources you have and making it work.”

The Power of Diversity:

Improving Profits Leads to Soil Health

HEMME BROTHERS FARMSTEAD CREAMERY — SWEET SPRINGS, MO

The three oldest Hemme brothers and their father were ready to welcome home the youngest Hemme son to the family farm in 2016.

However, they knew they would need to do something different on their row crop and dairy operation in Sweet Springs, Missouri. The operation was only supporting one full-time income, and adding a fifth person would be a tipping point.

The family evaluated their options. Either they could expand or add value to what they were already doing. They decided to start processing their own milk and making cheese to market directly to consumers. The move enabled the fourth brother to return to the farm, but Jon Hemme, the eldest sibling, says he just wasn’t satisfied.

We were hitting our yields,” Jon says, “but it seemed like there was never much left over, and it was disheartening.” Jon discovered regenerative agriculture and started down the path.

Though the dairy began as a grazing operation 20 years ago, the family had run into problems milking cows in the winter without housing. They built a barn and went the conventional, indoor dairy route, which included selecting cows that are big (bigger than even large beef cows, at 1,400 pounds). These cows are good milk producers but not necessarily efficient grazers. Now, the Hemmes are interested in moving back toward grazing — both for the sake of profitability and soil health. It’s a slow process, especially when considering smaller animals for the herd.

The Hemmes are already making headway in terms of their soil, however.

Their first step into regenerative agriculture was no-till. Just reducing disturbance to the soil gave them as much as a 1% increase in soil organic matter in eight years. About three years ago, they became more intentional about adding cover crops into their corn and soybean fields. In fall 2020, they planted oats and other forage species into a field of corn silage and started grazing it 60 days later for 10 days.

“The cows actually went up about 4.5 pounds in milk once we started grazing,” Jon says. “It was a really profitable deal that we were not expecting. Usually when you do something like that, the cows lose milk.”

Grazing cover crops does require a great deal of extra planning, Hemme says, but it also has the potential to save money. He estimates savings of about $35,000 per year in replacement heifer feed costs with the addition of grazeable covers. The cover crops also give the family’s limited perennial pastures a much needed break, allowing those acres to stay more productive longer. In time, the Hemmes are considering converting more cropland to pasture as they are able to add animals for cash flow.

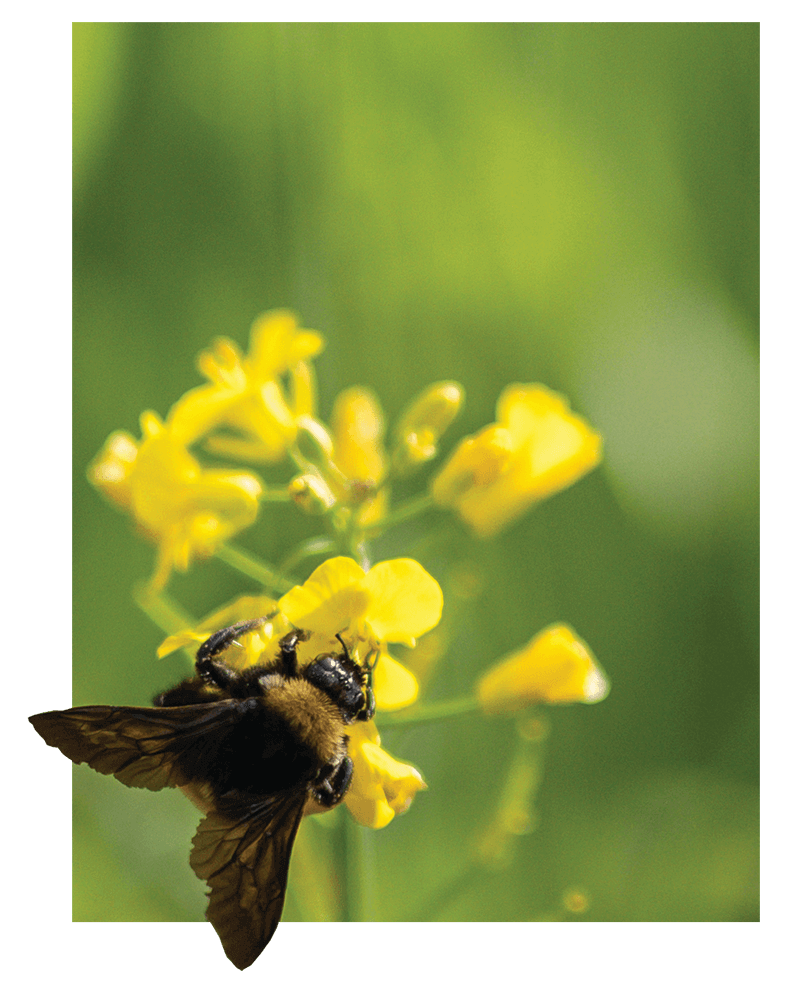

The Hemmes believe in the power of diversity, both in terms of the plants and animals on the land and the markets they channel their product through. The family has built their brand with cheese, but regenerative agriculture has helped them realize the opportunities are endless for new enterprises. They are testing pork fed with whey, a byproduct from the creamery, and are also raising pastured laying hens. Most recently, they added bees to the operation.

Their customers are happy with the improvements they are making on the land, too.

“Six years ago, this operation wouldn’t hardly supply a one-person salary with four people working there,” Jon says. “Today, the same operation supplies six full-time salaries as well as four part-time. As we add more enterprises, we can bring more people to our operation and have a positive impact in our rural community. It has far surpassed our expectations.”

Q&A With Jon Hemme, Hemme Brothers Farmstead Creamery, Missouri

What do you believe contributes most to your success?

Determination. When you want to see something work, you’re going to put more effort into it and, more than likely, it’s going to work. I also try to be pretty diligent in planning. Regenerative agriculture has forced me to do that. You have to think about what your rotation will be for the next year.

What is your greatest need on your regenerative journey?

I want to understand carbon-to-nitrogen ratios better and how to dial those in. Also, what is a good cool-season annual mix and what kind of biomass needs to be there to make managed grazing work well?

What advice do you have for someone just starting out on this journey?

Go meet people, because you won’t be able to figure all of this out on your own. Go to different conventions. Get out of your state to go to some things. If I hadn’t, I never would have met Jim Johnson, Noble Research Institute consultant. A lot of the people I have met have been helpful to me, and I only met them because I was willing to go out and meet them. That networking is extremely important.

What are Ecological Principles?

Regenerative agriculture will look different for each farmer or rancher because everyone deals with a different set of resources, climate, skills and operational goals. However, there are principles that transcend all of these details — these are the focus of regenerative ranchers.

Six principles of Soil Health

These six soil health principles are key to building up your soil health. The soil needs actively growing plants, vibrant communities of microbial species and well-managed animal grazing.

Know your context.

Know your individual situation, including your climate, geography, resources, skills and goals. You need to understand how the ecosystem processes function on your land so that you can work with those processes. What works for someone else may not work for you because your contexts are different. Find what works for you, but recognize your context is always changing. Be willing to learn, grow and adapt with it.

(Courtesy of Understanding Ag: understandingag.com)

Cover the soil.

Soil health cannot be built if the soil is uncovered or is moving. Using dedicated plants for grazing, cover crops and crop residue minimizes bare ground and builds soil organic matter. Plant cover further protects the soil from erosion and serves as a barrier between the sun and raw soil, preventing escalated soil temperatures that can destroy soil microbial life.

Minimize soil disturbance.

Mechanical soil disturbance, such as tillage, alters the structure of the soil and limits biological activity. If the goal is to build healthy, functional soil systems, tillage should only be used in specific circumstances. However, tillage is not the only disturbance. Grazing, fire, pesticide applications, etc., are all soil disturbances. For this reason, one must ensure with grazing lands that the timing, frequency, intensity and duration of these management activities are implemented in a planned manner mimicking what would occur naturally in the absence of man.

Increase diversity.

Increasing plant diversity first creates an enabling environment and catalyst for a diverse underground community. In nature, grasses, legumes and forbs all work together in a native, diverse rangeland setting. The complex interactions of roots and other living organisms within the soil defines the soil’s water holding capacity, affects carbon sequestration and enables nutrient availability for plant productivity. Managing for increased diversity can also be applied to grazing animals, wildlife, and other organisms above and below the soil.

Maintain continuous living plant roots.

Maintaining continuous living plant roots all year round is required to keep the soil biology processes working, no matter the season. Soil microbes use active carbon first, which comes from living roots. These roots provide food for beneficial microbes and spark beneficial relationships between these microbes and the plant.

Integrate livestock.

Research, practical application and common sense tell us the same thing: livestock are a necessity for healthy soils and ecosystems. The Great Plains evolved under the presence of animals and grazing pressure. Soil and plant health is improved by proper grazing, which recycles nutrients, reduces plant selectivity and increases plant diversity. As with any management practice, grazing is a tool that requires intentional application.

Working With Nature

There are four nature-made processes that drive how every ecosystem functions.

Think of a farm or ranch as an ecosystem. It is made up of soil, plants, animals, water, air and humans that rely on each other to exist, and is influenced by its unique climate and geography. No matter where a farmer or rancher lives, the land functions through these four interconnected processes:

Energy Flow

It all begins with the sun. Plant leaves are the solar panels that drive the energy cycle. The energy flow functions optimally when plants are allowed adequate recovery from grazing.

Water Cycle

The amount of water on Earth is finite, and it cycles through evaporation, transpiration and precipitation. One of the ways that water moves through the cycle is through its ability to permeate the soil.

Nutrient Cycle

In this cycle, energy and water are transferred between living organisms and the non-living parts of the environment. Frequent disturbances, such as grazing, help to maintain the aboveground nutrient cycle. Biotic activity such as eaarthworms, insects and microbes in the soil, further improve the nutrient cycle. An optimal nutrient cycle depends upon good plant diversity and soil cover.

Community Dynamics

Community dynamics are the changes to community structure and composition over time, including changes in microbiology, plant and animal life.

I understand now that every plant is an indicator of something going on in the soil and for the overall ecosystem. Before, I just saw those plants as weeds.

Sometimes I have to take a breath, step back and know that this a journey. I have to focus on what’s right and keep learning and working to improve.”Susan Bergen, Oklahoma and Texas

When Less is More:

Building Organic Matter, Building Resiliency

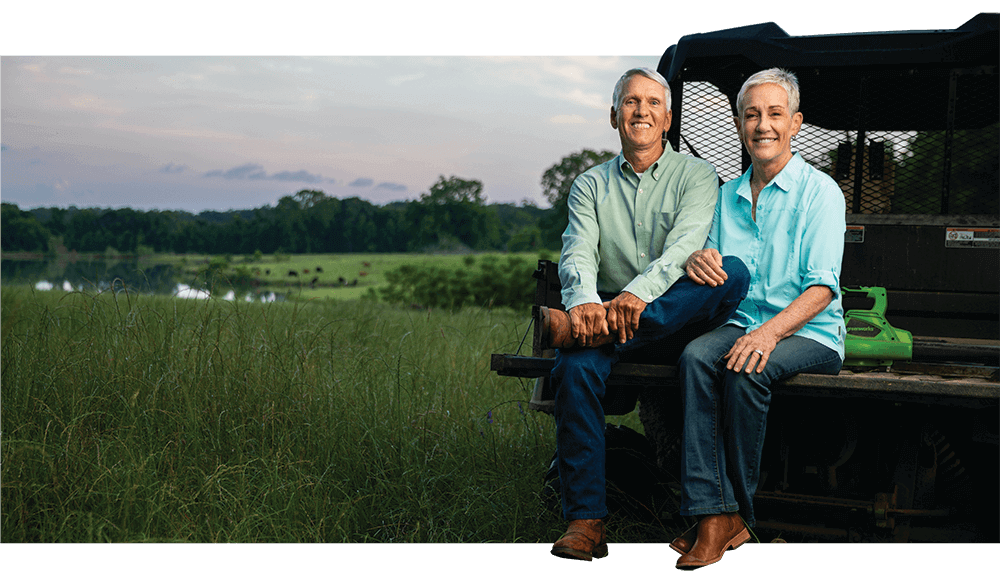

COOPER AND KATIE HURST — WOODVILLE, MS

Cooper and Katie Hurst, originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, bought their first piece of farmland in southwestern Mississippi, in 1990.

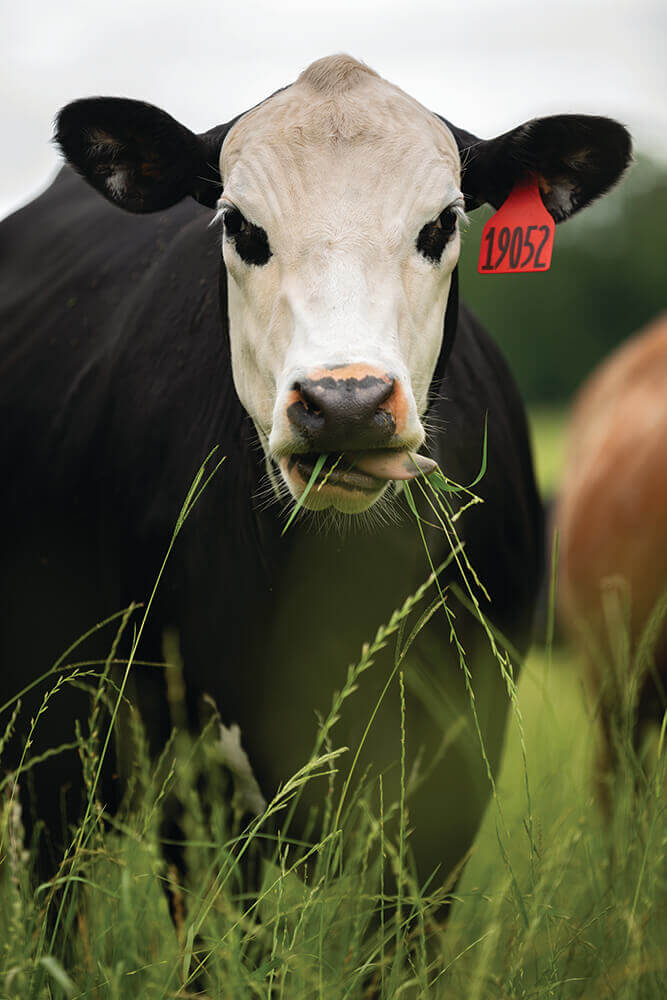

They began buying cows in 1995 and now retain ownership of their steers and heifers through the finishing process as members of the rancher-owned cooperative U.S. Premium Beef.

The Hursts always knew the cheapest way to feed cattle was by grazing. However, for their first 10 years in the cattle business, they grew their grass largely with the help of synthetic fertilizer. They viewed it as an investment in the land — which had been primarily worn-out cotton fields converted to pasture — and thought that over time they’d create their own fertility.

“We frankly found out that was not correct,” Cooper says. “We knew we had a problem, and we knew we had to change. At the time, I don’t know that ‘regenerative’ was the word we were thinking about, but we understood inputs. We wanted to end the never-ending increasing use of inputs.”

When the Hursts started out on the regenerative path, their first step was to implement a higher density, adaptive grazing system. They had always used a form of rotational grazing, but they consolidated their animals into one herd for greater impact.

“We saw the benefits quickly,” Cooper says. “We grew more grass and the cattle performed well.”

In conjunction with daily cattle moves, the Hursts saw the value of low-stress stockmanship. This, they say, improved both animal weight gain and health, including docility.

About eight years ago, the Hursts learned about the soil health principles and fully embraced them. Now, they are heavy users of cover crops, and they no-till drill every acre. They have living roots year-round, they always keep the soil covered with lots of diversity, and they graze high impact with long rest and recovery. They also no longer use synthetic fertilizer.

“I wish I would have known about this earlier because I literally spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on fertilizer up to that point,” Cooper says. “Regenerative ranching has been the best thing we’ve ever done. It’s taught us to think holistically and that everything is intertwined.”

Q&A with Cooper Hurst, Woodville, Mississippi

How has regenerative ranching impacted your ranch?

We really feel like we have become a lot more RESILIENT. We can’t make it rain, but we can make sure rain stays on our farm. We’re growing more forage on less rain with less money, and that’s the best testament I can give to regenerative ranching. And it’s only going to keep getting better, I’m convinced.

How has following regenerative principles benefited you?

We have basically been able to create our own fertility with the higher density grazing — the trampling of forage and the more-even distribution of manure, urine and saliva. We’re feeding microbes, and it’s the most natural cycle of life. Plants absorb the sun through photosynthesis and feed the microbes through the root exudates, and the microbes in return mineralize the soils and give the plants what they need. We’re not spending money on fertilizer. That was huge, not just financially but also mentally.

What would you tell someone just starting out in regenerative ranching?

Regenerative ranching has been, I would tell you, liberating. Besides financially great, it has reduced stress. We’re working with nature and not fighting it. Change is not something I like, but, also, at some point you usually figure out the definition of insanity. You can’t keep doing the same thing expecting different results. You have to change. No business is like it was five years ago. It’s the proverbial journey with no finish line, which is really good, because it just keeps getting better.

What’s the Big Deal About Soil Organic Matter?

Cooper and Katie Hurst have seen a tremendous increase in soil organic matter on their ranch in Mississippi after adopting the soil health principles and adaptive multipaddock grazing.

Like many farmers in the 1980s and 1990s, the Hursts were told they could never see a gain of 1% soil organic matter in their lifetime. However, in just 10 years of using the above-mentioned regenerative principles, they have gone from less than 1% to greater than 4% soil organic matter in some areas of their ranch. So what is soil organic matter?

Soil organic matter is plant and animal tissues in various stages of decomposition in the soil. As these plant and animal materials decompose, they leave carbon and nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, etc.) in the soil.

Nutrients feed the soil microbes and ultimately the plants. Microbes move throughout the soil, leaving behind glues that form soil aggregates. These aggregates are a key component of healthy soil structure. The spaces between the desired soil aggregates allow water and air to flow into the soil, holding moisture for later use (and creating habitat for certain microbes).

A 1% increase in soil organic matter enables the soil to hold 20,000 additional gallons of water per acre. Cooper Hurst also estimates that a 1% increase in soil organic matter gives him $700 in value per acre in nutrients.

Better water infiltration serves multiple purposes. It’s a safeguard against flooding, erosion and runoff. It’s also insurance against drought.

The Sight, Smell and Touch of Soil Health

Soil tests can help a rancher determine the health of their soil, but a rancher can also make their own observations. Simply take a shovel out to the pasture and dig up some soil, then take a look at the following five field indicators of soil health.

Color

Notice how dark the soil is. Generally speaking, the darker the soil, the higher the organic matter content. Soil is typically darkest in the uppermost layers of the soil profile, and it lightens as depth increases. Soil organic matter and soil organic carbon are primary drivers in biologically active soil systems.

Biological activity

Healthy soil is alive, meaning it’s biologically active. Look for earthworms, earthworm castings, dung beetles and evidence of other living creatures and their activity. Earthworms create burrows in the soil, which enables water to move down deeper into the soil. These burrows also create channels for roots to grow into. Earthworms and other insects, as well as soil microbes, also play important roles in nutrient cycling.

Soil structure

Soil structure is the arrangement of soil particles in different shapes and sizes. Look for soil aggregation, which is where soil sticks to itself and to the roots. Soil should stick to the roots even when shaken. Soil texture should resemble cottage cheese or chocolate cake. The soil should crumble easily and not simply turn to dust. When it gets wet, it should retain some of that crumble and not get so watered down that it would easily wash away.

Rooting resistance

Layers of compaction, or plow pans, in the soil are not desirable. These restrictive layers limit root penetration and water infiltration. Another sign of this issue is seeing “J” rooting, which happens when a root starts growing at a 90-degree angle after hitting one of these plow pans. This situation can cause forage growth limitations during drought.

Smell

Healthy soil smells fresh and earthy, thanks to an organic compound called geosmin. Geosmin is produced by active soil bacteria. The smell of unhealthy soil has been described by some as like hot copper pennies. Soil that smells like rotten eggs lacks oxygen and may be a sign of poor drainage.

Three rules of Adaptive Stewardship

Regenerative ranchers are adaptive and make decisions based on circumstances at hand. They operate with an understanding of:

Compounding

Everything you do — every decision you make and practice you apply — has more than just a singular affect. Everything on the ranch affects every other part of the ranch, from the water quality to the forages to the animal health to the economics. Decisions cannot be made in isolation because all things are connected and have ripple effects that may last years — positive or negative.

Diversity

Humans may like the look of a nice clean monoculture, but nature likes diversity. The soil needs lots of different fungi and bacteria, each of which may be attracted by a different kind of plant. Different animals also serve different functions, which, when you add up everything, creates a healthier ecosystem.

Disruption

One of the soil health principles is to minimize soil disturbance, especially minimizing or eliminating tillage, if possible. However, in general nature likes a few disruptions. The key to these disruptions is being intentional with how and why you’re introducing them. Some examples of intentional disruptions might be to change your cover crop mix or the order in which you graze your animals. You can’t do the same thing over and over and expect to find the most success. Remember, regenerative agriculture is not a prescription.

Our pastures stay greener longer into the winter and into drought. They’re more productive. They have more diversity.

I think that’s a testament to the overall way we farm. There’s not one silver bullet. It’s the rotation of the animals and the mix of the animals (cattle, chickens, turkeys and pigs). If we were just doing cattle, it would be difficult to do what we’re trying to do here in the Ozarks.”Cody Hopkins, Arkansas

Dealing with Difficulty:

Managed Grazing Yields Abundance

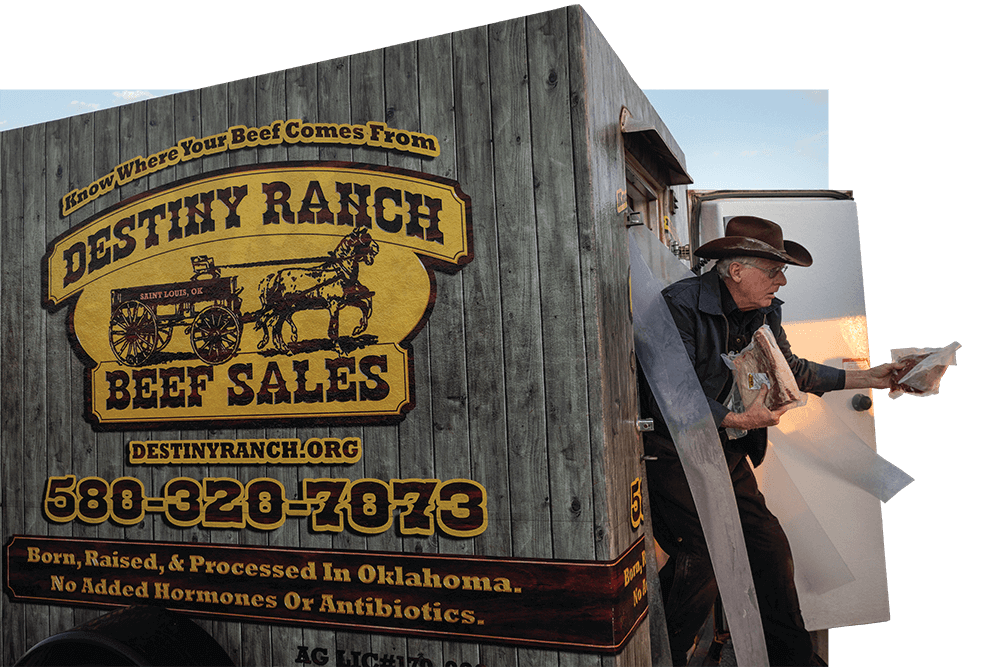

WILLIAM AND KAREN PAYNE — ST. LOUIS, OK

When William and Karen Payne first purchased and moved to Destiny Ranch in south-central Oklahoma, the land was overrun with brush and unproductive vegetation.

They set out to clear the land, give it rest, and then gradually add back cattle to jump-start fresh growth. A key to their success has been managed grazing. They’ve moved cattle every day, sometimes multiple times per day. After 15 years, the ranch near St. Louis, Oklahoma, has gone from being covered with little grass to abundant grass.

“For us, it’s like magic,” William says, adding that they have been able to double their soil organic matter in just 10 years on some parts of their ranch. “The organic matter is truly a big deal. If we graze too heavy, the grass may green up in spring, but it doesn’t produce as much. We keep quite a few records on which fields we come in and out of. We watch what has taken place not just this year but last year as well.”

The Paynes were watching closely at the dawn of 2020, knowing they were in the driest winter they had experienced since coming to the ranch. They had been leaving at least 6-8 inches of grass to protect the soil — one of their priorities since the beginning — and considering how to manage with limited forage. Then the pandemic hit.

The Paynes, who originally started as typical stocker producers selling to feedlots, now have a cow-calf operation and market all of their beef through retail markets in Norman and Shawnee. Demand exploded. At the same time, routine truck deliveries with supplies became delayed and so did operations at their processing plant. William started contacting people in the area who had lost their jobs in the oil fields and enlisted them to help bring in supplies. The Paynes also diversified the number of butcher shops with which they worked. Always, they kept a focus on the land.

“We cannot control what’s off the ranch, but we can certainly control what we have on the ranch,” William says. “We kept our priority with grazing and beef production.”

This long-term view of the land is what has given them their edge. Regardless of where they started, the Paynes have grass even when it’s dry and their neighbors don’t. They credit Noble Research Institute, one of the organizations they contacted first when starting the ranch, with helping them learn about their grasses and how to manage them.

“Our success overall at Destiny Ranch can be attributed to having access to Noble Research Institute consultants and education opportunities,” William says. “Nothing was a crystal ball, but the information furnished [by] and demonstrations at Noble Research Institute facilities have been invaluable to us.”

Q&A With William Payne, St. Louis, Oklahoma

What lessons from 2020 stick out in your mind?

The single most important lessons we were reminded of were to not get complacent from year to year and to not worry about the issues we cannot control. We have to stay on our plan and only make adjustments to long-term goals as a last resort. We absolutely know we can be flexible, but we must never lose sight of where we’re going.

How does being regenerative give you an advantage?

It is a huge benefit each day knowing that by taking care of the land on a regular basis, we have been able to increase grass production, which in turn allows us to increase pounds of beef produced per acre. We have greater control over extreme weather conditions. Seasonal planning becomes easier and allows us to concentrate on what matters most.

What would you tell someone interested in regenerative ranching?

Regenerative ranching is certainly a journey well worth taking. Starting is not hard, but it does take a different thought process. Take all the lessons you’ve learned from the past and blend in a few new thoughts and management techniques to make things really work. Start small and let your ranch evolve into what you want it to be. Take one step and see what happens, then take another step. Always remember this process does not happen overnight or in one season. It’s an investment in the long-term future, though it does not take a lifetime to start seeing some really great results.

What are the barriers to regenerative ranching?

Because it is a divergence from tradition, regenerative ranching can be challenging, especially in the beginning. What first seems uncertain becomes familiar, and risk results in reward.

Farmers and ranchers across the U.S. are finding innovative ways to overcome the barriers and find success. Noble Research Institute’s aim is to help farmers and ranchers overcome these barriers.

Four primary barriers to regenerative ranching

There are four primary barriers that often deter farmers and ranchers from adopting or using regenerative principles. These barriers include:

Lack of available, science-based management knowledge

There is a lack of fundamental, well- researched information that relates to production-scale systems of regenerative ranching. This leaves a vacuum of information and gulf of understanding, as many farmers and ranchers seek to understand the ecological principles that underscore positive land stewardship. With knowledge, however, comes the development and refinement of skills and a comfort and familiarity in practice.

Lack of guides and mentors

Knowledge or logic alone is not enough; it is only a starting place. A loss of motivation and commitment typically occurs when a person believes that a problem is too great and exceeds existing resources (e.g., knowledge, energy, time, finances). Everyone benefits by having a guide along the journey who cares about his or her success, helps connect the dots of understanding and provides encouragement when the unknown arises.

Economic uncertainty in adoption and operations as well as ongoing risk

Profitability is a practical reality of all professions. Farmers and ranchers need to make a living. Few if any enterprises can consistently cost more than they return. If ranchers cannot make enough to maintain their operations, they can lose their livelihood, their legacy and their children’s inheritance. An off-farm job should be an option, not a requirement.Furthermore, it is not enough just to get by. If producers are barely making ends meet, they often sacrifice long-term land stewardship practices for short-term returns. Thus, understanding the economics is essential.

Cultural/societal influences

Adopting regenerative ranching requires more than research, education and innovation. All decision-making processes involve a complex intersection of subjective factors that include culture, values, ethics, identity and emotions. These influences can operate within the individual rancher, in his or her household, or at the community level.

Noble as a Guide

Noble has built deep relationships with farmers and ranchers across the southern Great Plains since its founding in 1945.

Noble celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2020 and announced its plans to serve producers for generations to come by focusing all of its operations on regenerative ranching. The goal is simple: regenerate millions of acres of degraded grazing lands across the U.S. by directly working with farmers and ranchers across the nation.

“Every project, program or action Noble takes from this moment forward will be designed to build and sharpen a rancher’s knowledge, understanding and confidence in applying regenerative principles,” says Steve Rhines, Noble president and CEO. “We will be here when they need help or when they encounter something new. Our research will answer critical producer-guided questions regarding soil management, grazing, economics and business operations. Our educational and consulting programs will be rooted in equipping farmers and ranchers to effectively manage their operations using these regenerative principles.”

Noble has committed its 14,000 acres of grazing lands and livestock operations in southern Oklahoma, to provide education and demonstration for supporting others’ transitions to regenerative ranching. These acres will reveal both challenges and successes in Noble’s own regenerative journey, which Noble will openly share with others to benefit their own experiences.

“For 75 years, farmers and ranchers have been at the heart of our work,” Rhines says. “Our history has brought us to where we are. We remain obsessed in our mission to help producers be more RESILIENT. We are driven forward by a vision where farmers and ranchers can have lasting profitability today while ensuring the land for tomorrow.”

It really helps if you can find someone early on with a shovel who knows what they’re talking about and can show you that you’re making gains [to soil health].

I wish I would have put some soil in an air-tight bag when I started so I could see how much it has improved. I know there has been a world of difference.”Russ Jackson, Oklahoma

A Resilient Future

Adversity can happen at the most unexpected times and in the most unexpected ways. In 2020, society faced remarkable circumstances but proved its mettle. In the same way, a farm or ranch built on healthy soil better weathers the inevitable challenges to come.

Healthier soils soak in more water, using that moisture during times of lower precipitation or drought. Well-managed grazing deposits nutrients and stimulates forage growth, adding more green to the landscape and the bank account. Less dependence on inputs means more flexibility and freedom.

These outcomes, in turn, help the farmer and rancher steward the land, be profitable and leave a legacy. In the end, adversity is a constant companion, testing the spirit at every turn, but those who continue to find ways to learn, adapt and grow — they thrive. And, like rejuvenated soil, they are RESILIENT.

Join Us on the Regenerative Journey

This is a journey that is best traveled with others. Join us to learn from our experiences and to connect with others in regenerative ranching.

If you are interested in learning more about regenerative ranching, connect with Noble on our website or social media.

Support the land and its caretakers

Those who donate to Noble Research Institute become a partner walking alongside farmers and ranchers as they improve the land for future generations. Support the land and its caretakers by making a gift today.

To donate or for more information, visit www.noble.org/giving.

If we can stir people’s imagination as to the potentialities of the soil when conserved and built up,

Lloyd Noble, Founder, 1948

then the knowledge they would naturally acquire through these processes should materially contribute to increased confidence in themselves. As it is only when people have confidence or faith that they fight their greatest battles, if we assist them to this end, we will be reaching our objective.”

Comment