Compute and track your ‘reserve herd days’ to manage forage inventory and grazing

Knowing how to estimate forage inventories and actively manage grazing accordingly cuts down on hay feeding and protects both livestock and soil health.

If your grass totally stopped growing on a given day, how many more days could you sustain your herd on the forage you have standing in the pasture?

Hugh Aljoe refers to this calculation as ‘reserve herd days.’ The director of ranches, outreach and partnerships at Noble Research Institute says this is a valuable tally to track for anyone ranching on the drought-prone Plains, or for those who are simply trying to project dormant forage inventories into the winter.

“No matter where we are in the growing season, we’re tracking our reserve herd days,” Aljoe says. “No matter what the weather throws at us, we know whether or not we’ll have enough forage to get us through the winter. We always have a plan.”

That confidence in the face of drought conditions is the culmination of nearly 30 years of practice at the Noble Ranches. He points to two of his early mentors at Noble – R.L. Dalrymple and Charlie Griffith – who were masters at implementing and teaching the reserve herd day concept.

“They showed me this fuller picture, this idea of managing proactively, knowing all year long what you need to do to get to the next spring,” Aljoe says. “Then I really started to understand the value of our forage production throughout the year, that you can never have too much grass, and how to manage that production really effectively.”

Start by crunching your numbers

The goals in Aljoe’s mind are clear: “I don’t want to have to pay for hay. I don’t want to have to produce hay. I want to graze as long as I can, because on the ranch, it’s typically easier and cheaper to take the cattle to the forage than it is to take the forage to the cattle.”

Supplemental feed is the largest direct cost in most ranch businesses. If one of your regenerative goals is to kick the hay habit, Aljoe says, a good place to start is by tracking reserve herd days. Following this principle requires three fairly simple figures: days, demand and supply.

DAYS: Keep a count of the number of days until your spring forage flush, then add 30 more. If it sounds simple, it is. But counting it out will keep you honest about your needs. Each environment will be different, Aljoe says, but he shares Noble’s strategy for southern Oklahoma’s seasonal norm as an example.

“At Noble, we want to be 30 days into spring before we’re ready to be grazing fresh grass,” he says. “Spring growth will be growing amidst last season’s growth during those 30 days of grazing the overwintered forage, so transition to the high-quality diet is gradual. By the time they finish with the overwintered forage, the rest of the pastures have had time to recover fully and are ready to be grazed.”

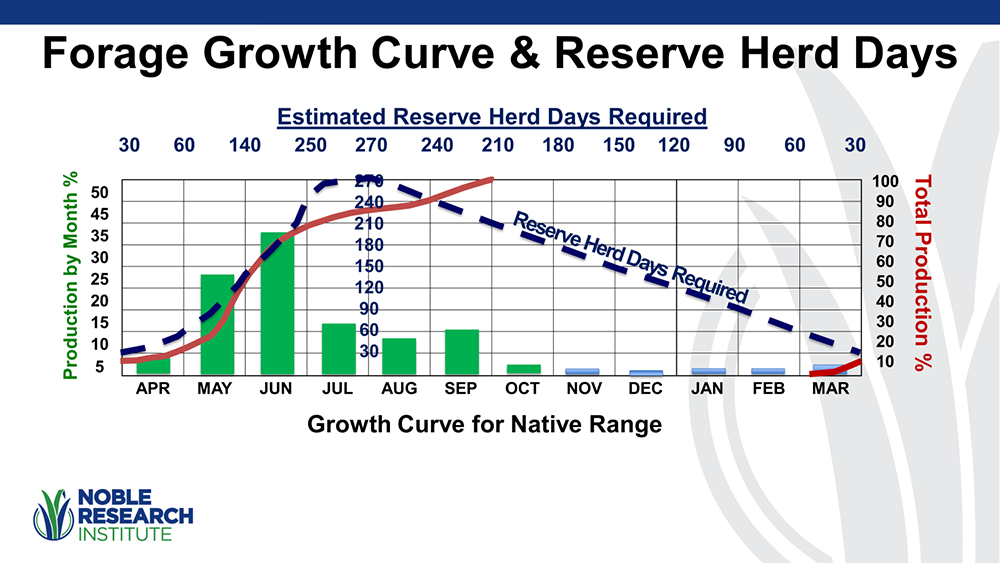

So, he counts backward from May 1, averaging 30 days per month, arriving at 180 necessary reserve herd days to get from Nov. 1, when native plants typically freeze or go dormant.

In order to have those 180 days reserved on Nov. 1, he knows that between May 1 and June 30, they better grow enough grass to provide somewhere between 240 to 270 grazing days’ worth of forage.

“So, I have to go from 30 reserve herd days on April 1 to accumulating 240 to 270 reserve herd days in early July,” Aljoe says. That puts a heavy expectation on the growth that occurs in that critical window. Monitoring the growth and regrowth that occurs in that window offers the key to the year-round grazing plan.

In a good rotational grazing program where there is a dozen or more pastures that the cattle are grazing through, one can estimate the number of days the cow herd could graze while maintaining the desired residual for each pasture. Total those days up and that is the number of your reserve herd days. Very simple if you are really into rotational grazing. However, most producers are not but the concept can still be applied by estimating forage demand and supply.

DEMAND: Aljoe suggests keeping the calculation of your livestock’s forage needs as simple as possible. Regardless of where she is in her cycle, a mature cow will need to eat 2.6-3% of her body weight in dry matter each day, so calculate conservatively at 3% to meet her at her greatest needs. For a 1,200-pound mature cow, that equals about 36 pounds of dry matter per day.

Be honest about the size of the cows you’re carrying, he cautions. The Southern Plains Experimental Range station in Harper County, Oklahoma, notes that over the past 60 years, mature cow size has increased an average of 7 pounds per year, with the average cow now weighing in at 1,350 pounds.

“The fact is, a lot of people’s cows are heavier than they think they are,” Aljoe says. “We might still have that 1,200-pound figure stuck in our heads, but they may well be bigger than that.” He suggests looking at your sale records from cull cows in recent years, tossing out the culls that ended up at the sale barn for poor condition, and average those who would offer a true representation of the herd.

For a 100-head herd of 1,350-pound cows, you’re looking at a demand of 40.5 pounds per cow per day, or 4,050 pounds of dry matter per day for the herd. (1,350 pound-cow x 0.03 = 40.5 pounds per day x 100 head = 4,050 pounds per day per 100-head herd).

SUPPLY: Your forage inventory calculation – the supply – can be as precise and complex as you desire. Get a grazing stick out or ask your local extension agent or rangeland conservationist to help conduct some clip-and-weigh inventories, if you want to check your numbers or fine-tune these figures.

But, Aljoe says, many ranchers can depend on their historical knowledge and trusted intuition to make these decisions, especially if they have been haying that ground in years past. The simplest way to calculate your inventory is to look at that pasture and think, ‘If I were to bale this today, what would I get from it?’

If you estimate you would harvest 2.5 bales per acre on that quarter section, and each round bale would weight 1,000 pounds, you have about 400,000 pounds of standing forage. (2.5 potential bales x 160 acres x 1,000 pounds = 400,000 pounds)

You don’t want to graze it to the ground, so make sure to run that total standing forage figure through the appropriate grazing utilization percentage. This is a quick estimate of how much of the forage you actually want to take in order to leave an appropriate amount of residue. For native pastures in the growing season, a safe estimate would be a 25% grazing efficiency, which would equal 100,000 pounds of grazeable forage inventory in the previous example.

This means your 100-head herd of 1,350-pound cows that needs a total of 4,050 pounds of dry matter per day has just shy of 25 reserve herd days standing in that pasture. (100,000 pounds grazeable forage inventory / 4,050 pounds of dry matter demand = 24.69 reserve herd days).

Success starts in the spring

A critical piece in all of these equations is using adaptive grazing to manage your residue and regrowth rate, Aljoe says, which changes throughout the year with rainfall and the season.

“We usually think about residue mainly going into the dormant season as ground cover,” Aljoe says. “But we really need to be thinking about it just as much in the active growing season. The residue you leave after a grazing event will determine how much and how rapidly that forage is going to recover.”

In peak growing season, the general rule of thumb has been ‘take half, leave half,’ but Aljoe says that requires more context.

“We’re supposed to be taking half of the leaf blade, not half the height of the entire plant. That’s a big, big difference.”

The portion of the leaves left after a grazing event during the active growing season are the powerhouse of the plant, fueling photosynthesis and regrowth. A grass like big bluestem boasts leaf structures 12 inches tall or more, but the bottom 4-to-6 inches of the plant is all leaf sheath on which the leaf blade grows. Taking half the plant would rob it of the leaves needed for rapid recovery.

If the goal is to accumulate 240-plus reserve herds days in that May-1-to-June-30 peak growing window, the approach must be to maximize regrowth rate while you graze.

“In our environment, I want to make a rapid rotation through all our pastures in peak growing season at least once, sometimes twice. If I’m really on top of it, we might get three grazing passes in some of those pastures during the growing season,” Aljoe says. Those peak season grazing events happen in quick succession on the Noble Ranches. The key is to “top graze” early in the spring with rapid moves and allow pastures to fully recover before re-grazing.

Aljoe says that compared to a continuous graze or simple rotation with a few pastures, he knows he can accumulate 30% to 40% more grazing days in the peak growing season if he is moving cattle on a daily basis. “I know not everyone wants to do that but stop and think about it: 30% to 40% more grazing days compared to even weekly moves. That’s huge!”

Think of it in terms of mowing your lawn – if you cut it high, you’re likely to need to re-cut more rapidly. If you shave it down close to the ground, it will take weeks to recover. The same is true in the pasture. The light, quick, ‘top-graze’ encourages re-growth, stacking on new grazing days behind each grazing event.

Monitor forward for most accurate assessments

This is where the idea of ‘monitoring forward’ comes into play, Aljoe says. After livestock move out of a paddock, the Noble team is monitoring regrowth rates.

“I want to make sure my grazing events two or three weeks ago had the outcome we intended, that the plants are fully recovering,” he says. “Then I can adjust my utilization rate accordingly.”

As recovery rates slow as the peak growing season tapers, Aljoe looks to shift from that super-light 25% utilization rate to a 50% or more utilization rate on dormant grasses. During the dormant season, we can graze most of the leaf blade material, but we must manage to keep plenty of after-graze material to cover the soil and protect the plant during winter dormancy.

“We’re varying our utilization rate depending on how fast and how rapidly our plants are growing, or if they’re growing at all. So, in the dormant season, utilization on the leaf area can be a bit more severe than we would allow during the growing season, because we’re not expecting that plant to recover until next spring.”

The key is to regularly monitor necessary reserve herd days against the actual forage inventory. The Noble team re-evaluates every two weeks. Especially during a drought, they check their bi-weekly inventories against key dates.

“I know that on June 1, I need to have about 140 grazing days already accumulated. If I’m only at 100, and it doesn’t look like we’re getting much more rain, I better start thinking about strategies to cut my demand,” Aljoe says. “If I hit July 1 and don’t have my 250 days accumulated, I know it’s time to start making decisions.”

Nothing feels like an emergency when you have a flexible plan in place, based on the current reality. That’s the kind of proactive management instilled by those early mentors, Aljoe says. Their decades of shared commitment to the principles have paid off as the native range has improved in forage production substantially.

NRCS soil surveys indicate some of the more productive soil types on Noble’s Coffey Ranch – where Aljoe started his career – should produce roughly 6,500 pounds of forage per acre in a favorable year.

“We go out there now, and we’re clipping and weighing forage production and measuring our grazing days, and we’re getting 8,000 to 9,000 pounds, in a drought year,” Aljoe says. While they keep a 30-day supply of hay on hand in case of extreme weather, the Coffey Ranch hasn’t fed hay for the past three years, even with drought conditions.

“It does take time,” he says, looking back to the almost 40 years of focused management that got them here on Coffey Ranch. He knows there’s still room for more improvement, too. It’s in the hard times, managed well, where they make the biggest leaps.

“When you have this kind of view across your pastures, you just don’t feel the same kind of pressure in the hard times,” Aljoe says. That doesn’t mean he takes the hard times lightly; he just knows the land is more resilient. “You know that what rains you do get are going to be effective; nothing runs off. You take good care of it, and the lands respond well.”

Comment