Regenerative Agriculture: Past, Present and Future

Ranchers are working on lands with hundreds of years of management history, which have influenced the ecological and economic challenges they face today. Regenerative agriculture is a long-term solution.

Regenerative agriculture and regenerative ranching are becoming increasingly popular topics of conversation, both in industry circles and in the media. This might lead you to believe that regenerative agriculture is a new management philosophy. However, this is not the case.

While the term “regenerative agriculture” was coined by the Rodale Institute in the 1980s, the principles and practices behind this movement existed long before then.

At Noble Research Institute, we focus on regenerative agriculture as it relates to grazing lands: regenerative ranching. Regenerative ranching considers the soil, air, water, plants, animals and humans as interconnected pieces of one whole system and aims to regenerate, or improve, that whole system.

Let’s take a look at the origins of regenerative ranching.

A Brief History of U.S. Agriculture

Native American Land Management

North American ecosystems were often managed using many of today’s regenerative principles prior to European settlement. Native Americans utilized many management practices that focused on harnessing the power of nature, from intercropping to the use of prescribed fire.

The Rise of Domestic Livestock Grazing

Moving forward, in the late 1800s came the expansion of domestic livestock grazing. At this time, many viewed our natural resources, particularly our grazing lands, as perpetually renewable resources, with little knowledge of the positive and negative impacts grazing management could have on plant communities.

In the decades to come, early conservation pioneers like Aldo Leopold, Arthur W. Sampson and Frederic Clements began to establish a better understanding of how our management impacts ecological health.

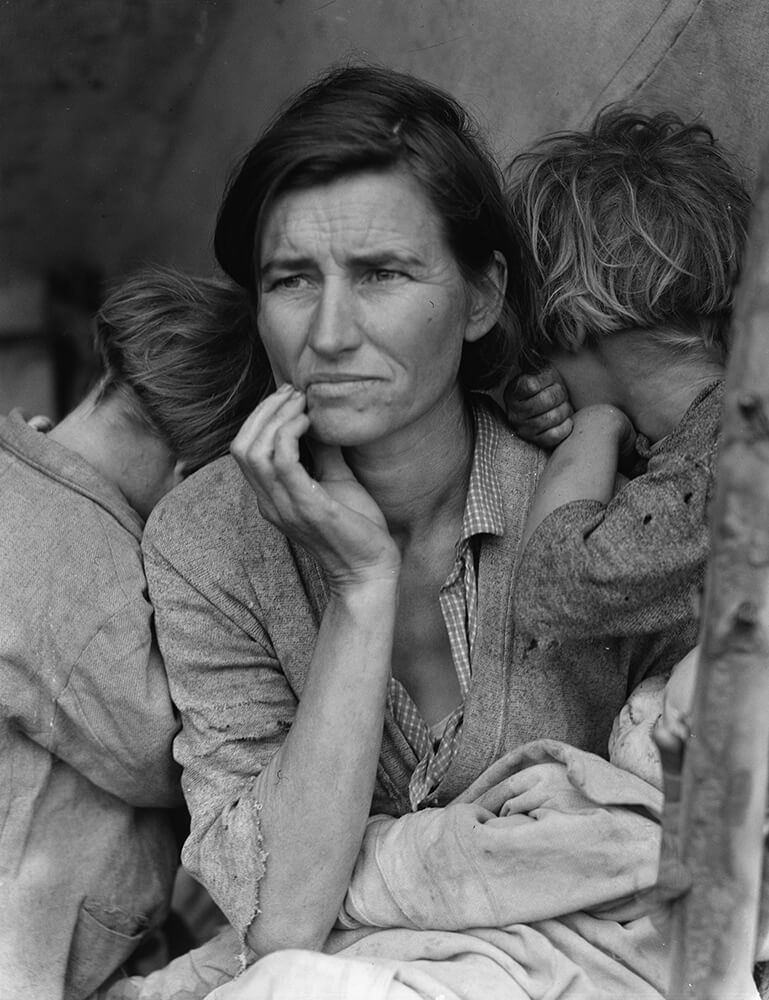

The Dust Bowl

Eventually, one of the greatest framers of conservation as we know it today grew from an ecological disaster we know as the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The devastating impacts of the Dust Bowl forced the federal government to act. At the urging of Hugh Hammond Bennett, they formed the Soil Conservation Service, today known as the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

The Dust Bowl had long-lasting ecological impacts, but it also had lasting effects on rural communities and economies, some that can still be seen today.

Post-WWII Synthetic Fertilizer and Technology

During the 1940s, the use of synthetic fertilizers and industrial technology began to change the face of agriculture by focusing production toward a product of increased inputs.

Modern Conventional Agriculture

Over the next 70 years, input costs would ebb and flow on an increasing trajectory. Agricultural production would focus on monoculture solutions, ultimately putting many producers in a compromising ecologic and economic position.

Regenerative Ranching Today

Today, producers are searching for regenerative solutions, and the origin of the principles may seem less important. However, in the end, many organizations have contributed to the lineage of regenerative agriculture, with many of those early principles we know and follow today codified by the writings of Robert Rodale.

The fact that these principles are not dependent on the type of land use and are foundational to ecologic understanding have helped them stand the test of time. Ultimately the context of each individual ranch (factors like climate, resources, and the rancher’s skills and overall situation) and the regenerative goals moving forward are what matter today. We are all working within landscapes shaped by hundreds of years of management history.

Looking to the Future

We still face ecologic and economic challenges in the ranching industry today. However, more and more producers are beginning to question tradition. Tradition, or more specifically “how we have always done things,” can be a useful tool if it is still applied within the same ecologic and socioeconomic context for which the practice was originally intended.

The trouble is that lots of things have changed in the industry, the country and even our local communities over the past couple of generations. Due to factors from increasing cow size to brush encroachment, the same practices that our predecessors applied to the land may or may not fit our current context.

Thus, tradition “for the sake of tradition” could be creating operational struggles. Many producers instead are blazing their own path forward, one that regenerates their landscape, is economically successful and promotes their chosen quality of life.

Qualities of Today’s Regenerative Ranchers

Today, regenerative-focused producers are harnessing the power of nature instead of fighting it. They are continual learners, honing their ability to “read the land.”

They have an instinctual need to further understand how plant communities, biodiversity, soil health metrics and livestock production work together and respond positively or negatively to climate fluctuations and their management. They further appreciate that production does not have to be at the expense of the land, and that cost and value are two different things.

Regenerative-focused producers today view management practices as tools. Each tool or practice has a specific purpose and can be effective if used within the right context. However, the concept of Maslow’s hammer: “If all you have is a hammer, everything begins to look like a nail,” is all too often an outcome if tools are not viewed as part of a greater toolbox.

Within the context of wildlife management, Aldo Leopold in Game Management stated, “The central thesis of game management is this: game can be restored by the creative use of the same tools which have heretofore destroyed it — axe, plow, cow, fire, and gun.” The same process holds true for landscapes. The same “practices” that have been used to damage land can be used in the right context to regenerate it.

Today’s regenerative producers are motivated by outcomes and use technology to enhance understanding of the systems they manage, rather than as tools aimed at increasing production alone.

Many regenerative producers understand that increased production is not always directly correlated with net profit. Often, reducing excessive inputs can have a greater impact on net profitability of the ranch as a whole.

Regenerative producers are focusing more on technology that helps them both keep good records and understand the metrics of their management. It’s often said that “you can’t manage, what you don’t measure.” Many progressive producers are using grazing management technology platforms to better understand their grazing metrics.

Changing Markets and Increasing Demand

Today’s regenerative producers are becoming more interested in producing a product than a commodity. The climate of today’s commodity-driven agricultural landscape has pushed many producers into being “price takers” rather than “price makers.”

More and more regenerative producers also are vertically integrating their enterprises and focusing more on marketing in order to provide a product with a story.

You can see this in people who directly market beef to consumers themselves or in those who join up with larger cooperatives or companies to produce and sell their beef in a way that the consumer understands it was raised in a certain way, like on grass its whole life, or without antibiotics. These regenerative products are seeing a boost in demand locally, regionally and nationally.

Ultimately, regenerative producers are keenly motivated to put their ranch to work for them rather than them working for the ranch. They concurrently understand that regeneration is a needed outcome due to prior decades of improper management. They understand that regeneration is a journey not a destination.

The Future of Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Ranching

The idea of managing ranches with a focus on building healthy soils and implementing management that promotes healthy wildlife populations and their habitats, biologically diverse plant communities and livestock production is not a new concept. It is, however, a concept that depends on producers who are driven toward those outcomes.

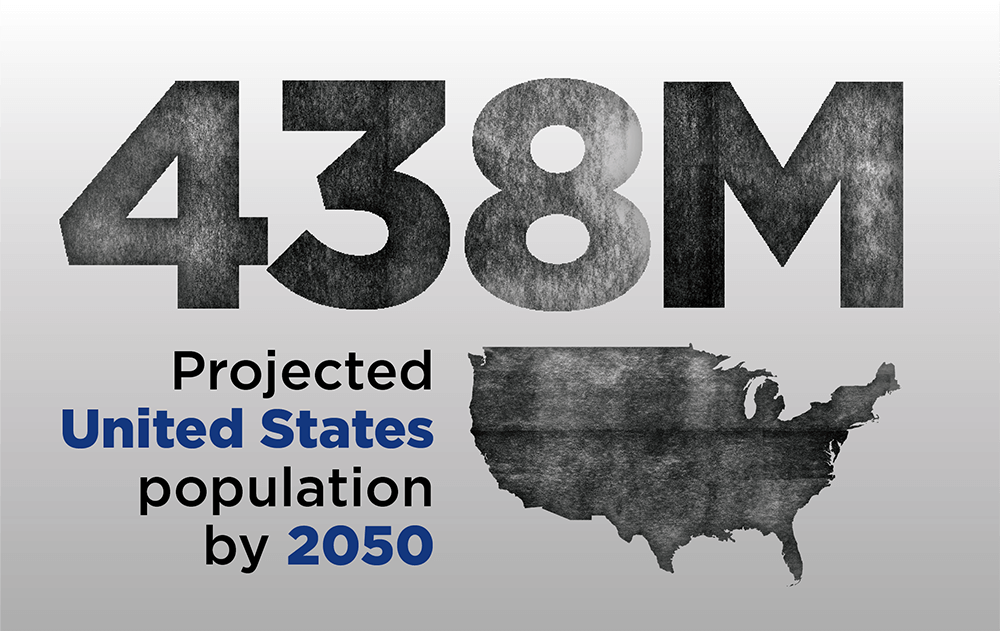

As we look to the future, the external challenges facing U.S. producers will only become more intense. As the U.S. population grows toward a predicted 438 million people by 2050, the demand for food and land will increase.

Many questions are currently being asked. Do we continue to promote management that maximizes production on smaller acreages at the expense of land health, or are there alternative strategies that are productive and profitable while regenerating land?

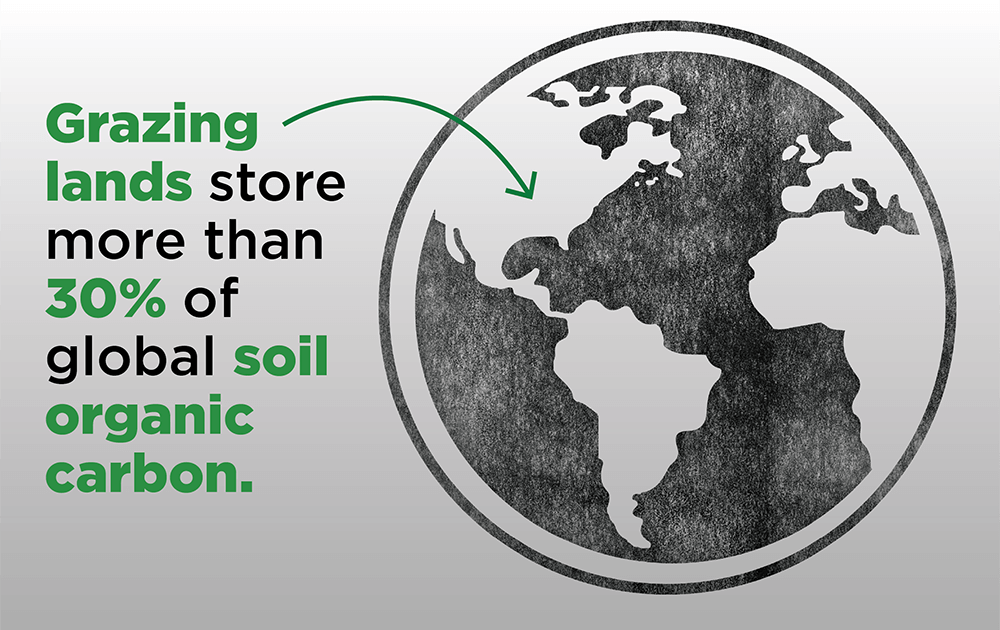

The majority of our grazing lands are generally not well suited for cropland food production, yet they serve our planet by storing more than 30% of global soil organic carbon. Such intrinsic outcomes are called ecosystem services. Ecosystem services are the many and various benefits provided to humankind by healthy and functioning ecosystems.

Ecosystem Services: A Marketplace for Regenerating the Land

Leopold once famously stated, “Conservation will ultimately boil down to rewarding the private landowner who conserves the public interest.” Opportunities to compensate producers for the production of multiple ecosystem services are currently in development. Ecosystem services are often grouped into functional areas of soil, air, water, plants and animals.

Many of the questions around the production of ecosystem services are common to most emerging markets, and these questions are not lost on regenerative ranching. Largely, much of the research focus in the future will be placed on which metrics matter, how do we most aptly measure them, how are they influenced by management, and can they be monitored at scales that are relevant to producers?

One of the cornerstones of regenerative ranching is a focus on diversifying products, therefore the diversification of market opportunities will continue to be an option for producers interested in regenerating landscapes.

With more data comes more understanding of the value of ecosystem services: how they could be a potential revenue stream and how they impact increased health and function on existing production enterprises.

Managing regeneratively allows our living soil to sequester organic carbon, which aids in climate mitigation strategies. Increasing organic matter provides our soils a greater ability to build aggregation, which allows it to hold more water and further serve as a filter to increase water quality and quantity. Biodiversity is also an outcome, from the soil microbiome to more functional habitats for wildlife species. These are all services provided by regenerative producers that benefit society as a whole.

Regenerative ranching has a positive future. More and more producers are questioning their conventional methods, measuring their outcomes and defining goals that include regenerative solutions. These are and will continue to be positive developments for the agriculture industry and for society as a whole. The question we should all ask ourselves is, what would a future look like without regenerative ranching?

Comment