How To Help – and Not Hurt – Nature’s Recycling System: The Nutrient Cycle

If we mimic how nutrients are cycled in natural grasslands, we’re off to a good start.

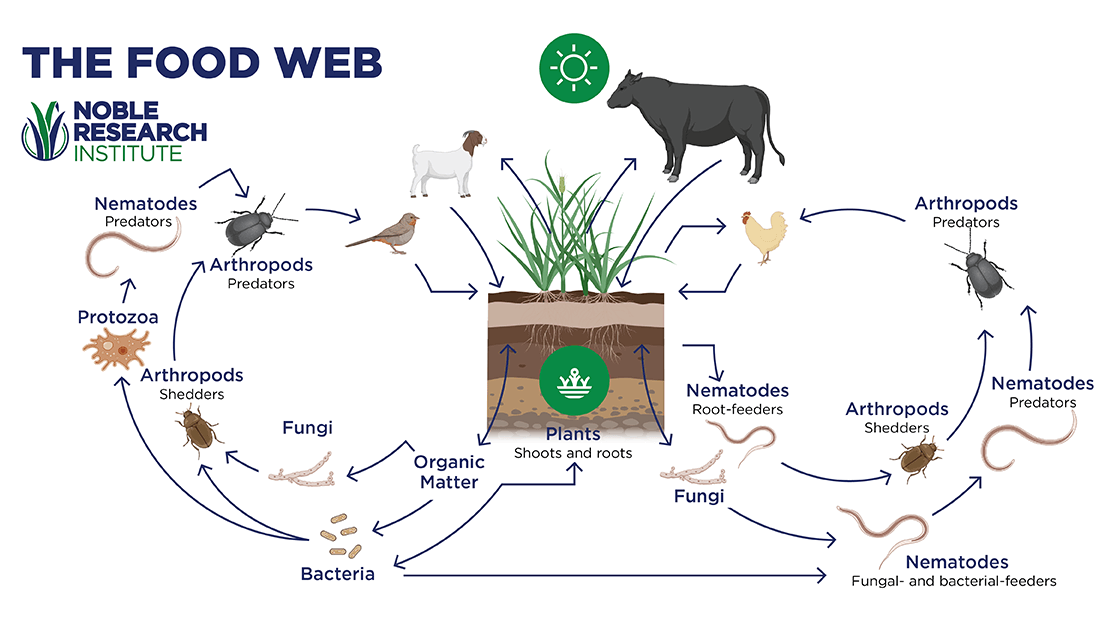

In grazing land, the nutrient cycle, sometimes called the soil food web, has many interconnected players and processes. As land managers and ranchers, what is our part in enhancing activities above and below the soil to make nutrients available to plants and animals?

Simply put, our job is to do what we can to mimic how nutrients are cycled in natural grasslands, and then stay out of the way so we don’t short-circuit the cycles. Let’s look at how this works.

The nutrient cycle

First, the cycle. All the essential nutrients for plants and animals already exist in the soil, air or water. The soil contains many nutrients, from boron to zinc. The air has nitrogen, carbon and oxygen; and water has hydrogen and oxygen. Sugars and fats are made of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Add some nitrogen, and you have the base to start making amino acids, which form proteins. So, we have everything we need to feed the soil food web, which in turn feeds the plants and animals that feed us.

Through photosynthesis, plants provide food for humans and other animals with their seeds, leaves and roots. Looking more closely at plant roots, we find that as they are growing, they exude or leak sugars and other substances that also feed soil bacteria and fungi that can’t photosynthesize and make sugar for themselves. This is an important gift provided by green plants.

In return, microbes, such as mycorrhizal fungi, play a big part in supplying nutrients to plants. These fungi can mine nutrients from the soil minerals and make them available to plant roots. In exchange for the plant nutrients, the fungi get sugar from the root exudates. Some mycorrhizal fungi can even broker the trade of water and nutrients between living plants and, in return, get sugar from both.

Another way nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur are made available to plants is through the death and decomposition of bacteria and fungi, which allows their nutrients to be taken up by plants. Alternatively, when bacteria and fungi are consumed by a higher-level microbe like protozoa or nematodes, those microorganisms excrete their wastes as plant-available nutrients. The cycle continues when those organisms die and decompose, leaving additional nutrients for plants, or when they’re consumed by an organism higher up in the food web, like an earthworm or an insect.

Many plants in our pastures have special talents that make nutrients available to other plants, such as legumes that fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, and deep-rooted plants like forbs that mine nutrients from the subsoil. Even if a cow doesn’t eat certain plants, she can still trample some of them onto the soil surface where shredders like beetles and springtails help break them down. This allows bacteria and fungi to access the nutrients to help feed a new crop of desirable plants.

Continuing the cycle, a range of animals eat the plants, including ruminant grazers such as cattle, sheep and goats; deer, elk and bison; non-ruminant herbivores like rabbits and beavers; omnivores like quail, chickens and turkeys; and even grasshoppers and other insects that nibble on plants before being eaten by a snake or a hawk. Eventually, all of these excrete their wastes or die and recycle their nutrients, feeding the food web again.

How to help the nutrient cycle

There are several management practices ranchers can use to mimic natural grasslands and optimize a healthy, robust nutrient cycle on their land.

- Keep a diversity of plants with actively growing roots in the soil as many days of the year as possible.

- Manage for healthy plants by testing your soils and plant tissues and then amending the soil as needed, especially keeping the soil pH in an acceptable range.

- Use regenerative grazing to be intentional about forage removal, animal impact and manure distribution.

- Incorporate a diversity of animal species to graze a range of forage plants as well as to distribute a variety of manures and urines.

- Make sure much of the ungrazed plant material is trampled down and put in contact with the soil so the soil organisms can recycle those nutrients.

I can’t overemphasize the importance of diversity – in plant species, animal species (grazing or not) and soil microbiology. The more diversity we have, the more functional the nutrient cycle will be.

Things to avoid

Here are the major things to avoid if you want to keep the nutrient cycle functioning:

- Avoid tillage, because it is devastating to the soil microbial community.

- Avoid excess removal of nutrients. The two biggest culprits here are haying and erosion. Yes, grazing pastures removes some nutrients, but the amount of nutrients leaving in a carcass of beef are insignificant compared to what leaves in a ton of hay or is lost through topsoil erosion.

- Aim for plant diversity rather than monocultures. Both soil biology and livestock benefit from the balance of nutrients they can get from a diverse, natural diet.

- Limit or avoid the use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, which can short-circuit the nutrient cycle.

On that last point, some think we must fertilize to grow plants, but there are plenty of plants growing in road ditches, national parks and other places that are never fertilized. It’s not a lack of fertilizer that limits plant growth, it’s a lack of nature functioning like it should. And typically, we’re the ones who have short-circuited it.

How to know the cycle is working

So, how do we know if the nutrient cycle is functioning well on our land? One of the best ways to know is to analyze your soil’s fertility and health with the Haney soil test, which measures the quantity of soil nutrients available from both inorganic and microbial sources. Plant tissue tests can be another measure.

Field observation is another tool. Are your desired forage plants healthy and green? Or are you seeing indicators that can signal problems with the nutrient cycle? For example, oldfield threeawn thrives in areas so low in nutrients that other plants struggle to grow, so seeing it dominate an area is typically a warning sign that something is wrong with the phosphorus (P) or potassium (K) cycle. Broomsedge bluestem is another indicator plant that tends to appear when there’s trouble with the P or K cycle and/or the soil pH. Undecomposed manure pats and plant residues that last for months or even years are yet more indicators that something is dysfunctional in the nutrient cycle.

The bottom-line indicator of a healthy nutrient cycle is when your plants, livestock and wildlife are healthy, thriving and producing well. Productive, regenerative and resilient ranches and farms are the ultimate pay-off of enhancing nutrient cycling in your pastures.

Comment