Category: Regenerative Agriculture

Categories

Why You Need a Grazing Plan and How to Start One

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Taking time to make and follow a grazing management plan pays many dividends.

Improving versus Maintaining

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Regenerative ranching builds natural resources.

Putting Soil Health First

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Health below the ground is key.

Intentional Improvement

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Keys to successful regenerative grazing.

Choosing Nature’s Calving Season

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Noble Ranches have increased cow-calf enterprise gross margins by shifting spring calving two months late...

Low-Risk Strategies to Transition from Conventional to Adaptive Grazing

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Starting small and using what you have are ways to ease into regenerative practices.

What Your Grass and Cover Crop Seeds Need to Succeed

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

The health of your soil and a few core principles lead the way to good germination

Farming at a Human Scale

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

In the heart of the Adirondack Mountains, a couple revives pastures with grazing and compost.

Building Your Grazing Community

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Find like-minded farmers and ranchers to support your regenerative grazing goals.

Sharing Your Ranching Story on Social Media

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

How to build community and connections by posting stories, photos and videos of your regenerative journey

Simple ways to measure soil health improvements in real time

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Tap into your observational senses to mark progress anytime you’re out in your pastures.

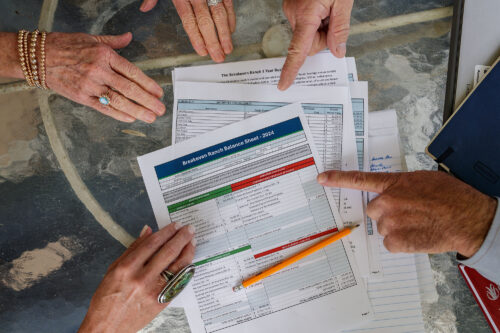

Identify new management practices for better profitability

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

Learn how to assess costs, set profit targets and adopt regenerative practices sustainably with help from...

Compute and track your ‘reserve herd days’ to manage forage inventory and grazing

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Knowing how to estimate forage inventories and actively manage grazing accordingly cuts down on hay feedi...

How to extend grazing days with fall cover crops

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Ranching advisor Jim Johnson breaks down a common question he hears from ranchers – how to incorporate...

Four ways feral hogs cost farmers and ranchers

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Learn to recognize signs of these invaders, what’s at risk and what you can do to control their populat...

Sweet Tamarind Chili Steak

Estimated reading time: 1 minutes

Expertly crafted in the Certified Angus Beef® brand test kitchen, this recipe offers a delectable fusion...