A Tale of Two Ranches

A five-year study by a Noble Research Institute team examines how the contrasting ecosystems of Noble's Coffey and Red River ranches respond to regenerative grazing management.

It’s a mere 10-mile drive between two of the Noble Ranches that sit in southern Love County, Oklahoma, just north of the Red River that separates Oklahoma from Texas.

Despite their close proximity, the context and ecosystems of the Coffey Ranch west of Marietta and the Red River Ranch south of Burneyville are as different as night and day. Given the dissimilarity in their soils, topography, use history and the forages and crops grown there, the two ranches are an ideal study in contrasts for a team of Noble Research Institute researchers studying how rotational adaptive grazing and reduced reliance on fertilizers and herbicides are affecting the two environments during the five-year study period.

Basically, the researchers consider the ranches to be two different contexts – Coffey with a long history of rotational grazing on mostly native rangeland, and Red River as “introduced” pasture where former cropland was planted to bermudagrass seven years ago and fertilized and sprayed for hay production until late 2020. That’s when rotational grazing with cattle started on both ranches, along with reduced reliance on fertilizer and herbicide use.

Having these two contrasting systems will help Noble understand more about how regenerative management affects the soil microbiomes and nutrient cycling processes in grazing lands. The research goals are not only to learn all they can about how pastures on the two ranches now respond to the same regenerative strategies and practices, but also to learn more about the drivers of soil health. Their work could help unlock secrets of just how the plants and the community of microbes below ground interact and ultimately create more organic matter in the soil.

“We are testing the regenerative strategy as a way to improve soil health. What we are targeting is understanding the microbial community, but also the changes in the plant community, in order to quantify and understand the drivers of soil health,” says Eloa Moura Araujo, a postdoctoral fellow at Noble and the soil and statistics member of the team.

“We are trying to understand the processes that happen and what players are responsible for the change, if we have changes” in organic matter, she says. “By understanding the process, maybe it can help you make better decisions in the future.”

Part of a Statewide NSF Research Project

Araujo; Myoung-Hwan Chi, Noble research lab facility scientist; and Maira Sparks, Noble research associate, are conducting the research under a National Science Foundation grant that is funding a statewide Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) project in Oklahoma. The overall project, “Socially Sustainable Solutions for Water, Carbon and Infrastructure Resilience in Oklahoma,” draws on expertise from more than 40 researchers in a socialscience-led, multi-disciplinary collaboration of social, physical, biological, engineering and computational scientists from university and other research organizations in the state.

Chi is the primary investigator for the work at Noble, which falls under the Terrestrial Water & Carbon Dynamics focus of the NSF EPSCoR project. His area of expertise is plant microbiology, looking at the biomass levels and diversity of individual organisms making up the soil microbial communities. Sparks takes the lead in studying the above-ground plant community.

Isabella Maciel, systems research manager at Noble, says one of the reasons why having a diverse system is important is the hypothesis that vegetation diversity also helps the diversity and vitality of the microbes in the soil, and ultimately, soil health.

“We are tracking everything we do now to try to understand if there is any connection between what you are seeing above ground and what is happening in the soil,” she says.

Toward that end, the team has set up 18 sampling sites per ranch, three triangles marked with posts in each of six pastures at Coffey Ranch and six pastures on Red River Ranch. Three times during the growing season (spring, summer and fall), they sample and perform vegetation assessments. They take soil samples two or three times a year, waiting to pull soil cores until two to four weeks after the cattle are moved out of the sampling area.

To assess what plant species are growing in the pasture and at what frequency, they establish a transect (line) and place a rod in the ground. They record all plant species touching the rod. The process is repeated at 6-inch intervals at 46 points along each of five 23-foot transects at each sampling site, for a total of 230 points of plant population data collected each time.

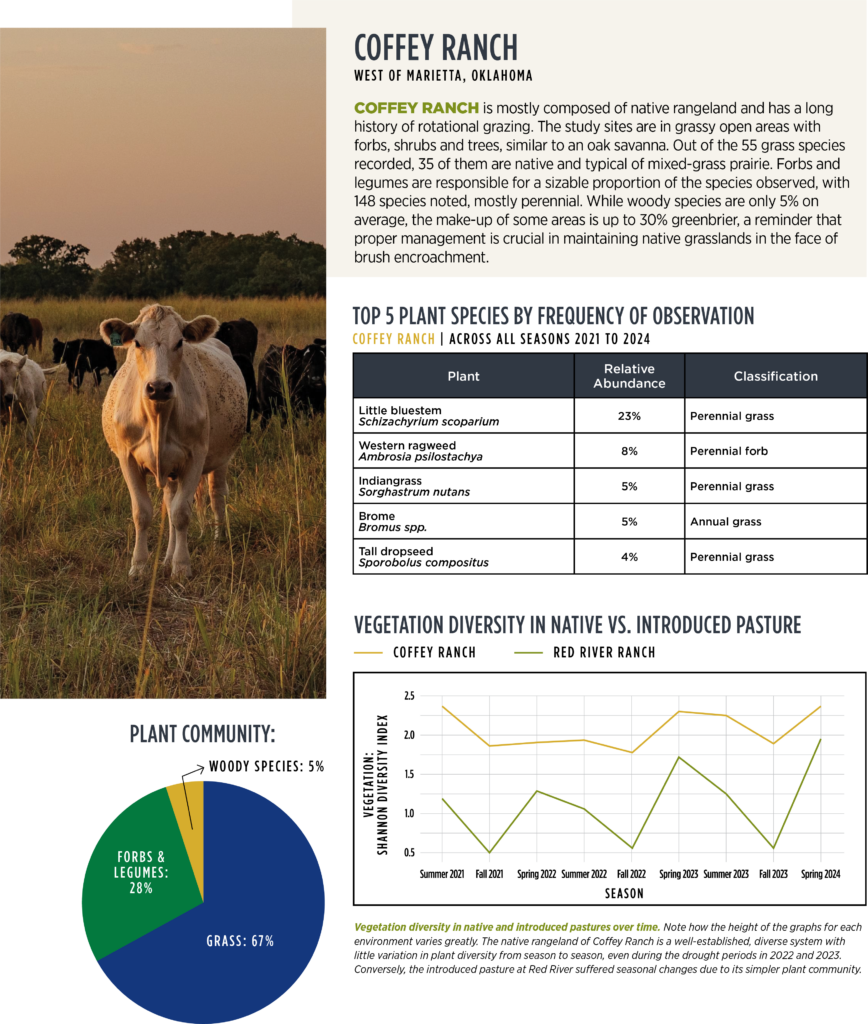

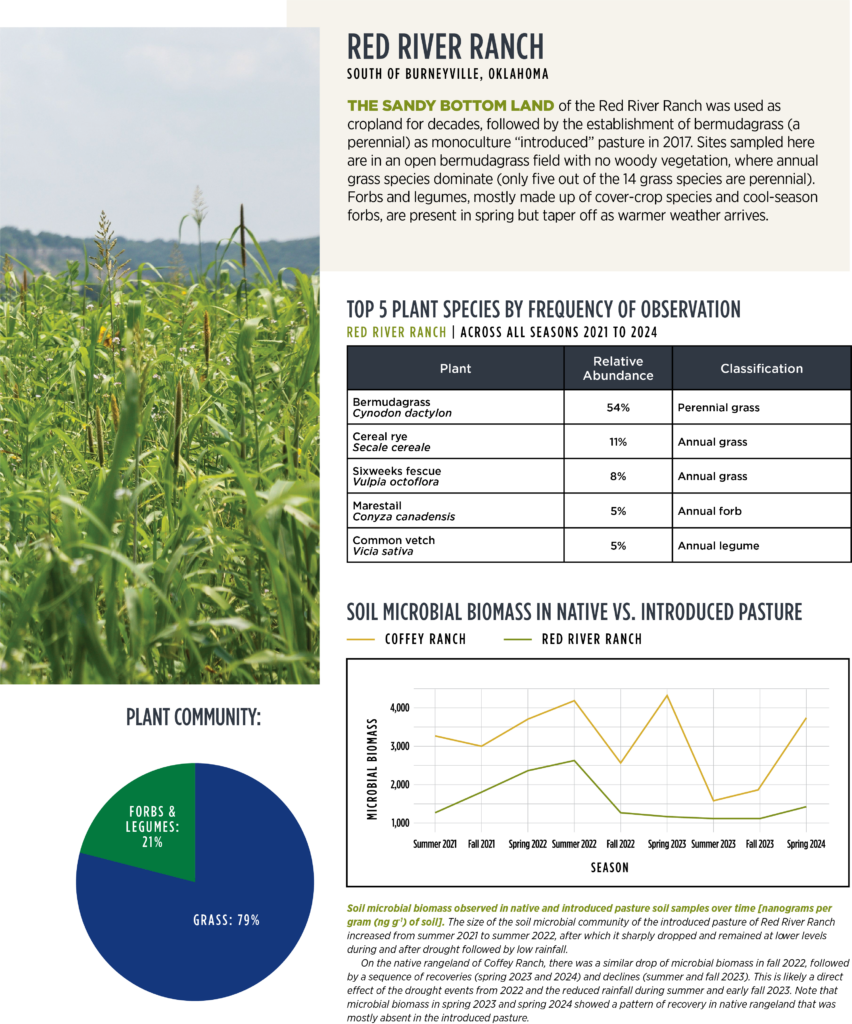

At Coffey Ranch, the team has recorded 55 grass species, 35 of them native and typical of a mixed-grass prairie. All grasses make up 67% of the community. Forbs and legumes in 148 species have been recorded there, mostly perennial. The number of woody species varies depending on the pasture. (See the top five species on pages 6-7.) At Red River, grasses dominate at 79%, with bermudagrass being the most abundant out of only 14 grass species ever recorded there.

From the soil samples, Haney tests show multiple aspects of the soil health; phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) tests quantify functional groups of

microbes, like bacteria and fungi; and DNA sequencing identifies the individual microbes that make up the community. Between soil and vegetation measurements, the team assesses a total of 100 variables three times per year.

Tracking Resilience Over Time

Long-term monitoring studies like this allow Noble to detect seasonal differences and trends over time so the team can explore how multiple factors — such as grazing strategies and the weather — affect the key indexes they are studying. The graphs in the infographics below illustrate some of the seasonal changes already observed and how they differ between the two ranch ecosystems.

For example, one important indicator of soil health is the total microbial biomass, a valuable metric to represent the size of the soil microbial community. Overall, the greater the community (more microbial biomass), the more functions can be performed by the soil, like nutrient cycling, turnover of organic matter and regulation of pathogens.

While it is too early to draw definitive conclusions from results to date, the team has observed differences in the microbial biomass between the two ranches and is investigating to discern the composition of the microbial communities. They know that key players in the microbial community in the introduced pastures at Red River shut down and the whole community decreased during drought, indicating it was sensitive to extreme events and needs long recovery periods.

At Coffey, under the same climate stress, the microbial community in the native pastures were able to better absorb the stress and recover faster after periods of dry weather. This suggests that the native pasture could be more resilient to disturbances such as drought.

Noble Research Benefits Ranches and Ranchers

The NSF EPSCoR research is just one of many ongoing studies Noble scientists are conducting on Noble Ranches and beyond.

Noble is co-leading a multi-institution team investigating grazing management systems and their impact on ecosystems and producer well-being. The 3M project (full name: Metrics, Management, and Monitoring: An Investigation of Pasture and Rangeland Soil Health and its Drivers) is a five-year, $19 million endeavor monitoring ecosystems on participating rancher sites in multiple states as well as on Noble Ranches and properties owned by the University of Wyoming and Michigan State University. Ecological samples include soil cores, forage samples, energy flux measurements and water impact-related measurements.

In other work on Noble Ranches, the Noble Transitions Team is recording data from soil and water infiltration tests as well as surveys of vegetation, insect and wildlife populations across all six ranches to monitor changes over time following the transition to regenerative management practices in 2021. The team hopes to put “hard numbers” to what’s happening in the ranch ecosystems now that chemical inputs are no longer used and adaptive, multi-species grazing is in use. A key benefit will be learning which of the many tests they’re conducting delivers the most valuable information and also which are the easiest and most economical for ranchers to do.

Comment